What we know about teacher shortages

Paul Bersebach/MediaNews Group/Orange County Register via Getty Images

What we know about teacher shortages

Students walk to class during the first day of school

The COVID-19 pandemic has proven to be a particularly grueling time for teachers. School districts seesawed between in-person, remote, and hybrid learning, forcing educators to adapt quickly to an environment often not conducive to learning, nor allowing them to provide the best educational model for students of all needs. Moreover, many teachers worried about their own health, particularly as restrictions began to ease and students returned to classrooms.

One unfortunate result has been that teachers are leaving the profession in droves. Among public school teachers who stopped teaching after March 2020 but before they were scheduled to retire, almost half did so because of the pandemic. COVID appears to have increased the stress of an already stressful job.

Of further concern is the fact that there have simply not been enough new teachers to take their places. A survey released in February 2022 by the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education found that in both the fall of 2020 and the fall of 2021, 20% of undergraduate-level teaching programs saw a drop in enrollment. At the graduate level, 13% of institutions had a significant drop in enrollment in 2021. Furthermore, wages that are not keeping up with inflation—combined with increased levels of stress and anxiety—are forcing some teachers from the profession.

A working paper from Brown University’s Annenberg Institute released in March 2022 cautioned that limited data had “led to considerable uncertainty and conflicting reports about the nature of staffing challenges in schools.” Joshua Bleiberg, one of the paper’s authors and a postdoctoral researcher studying school reform, told Vox, “There are so many different measures of teacher shortages, and there’s no national standardized definition of what a teacher shortage is.”

To explore this issue, eSpark looked at the numbers behind teacher shortages, citing data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Department of Education’s Higher Education Act Title II State Report Card System.

![]()

ESpark

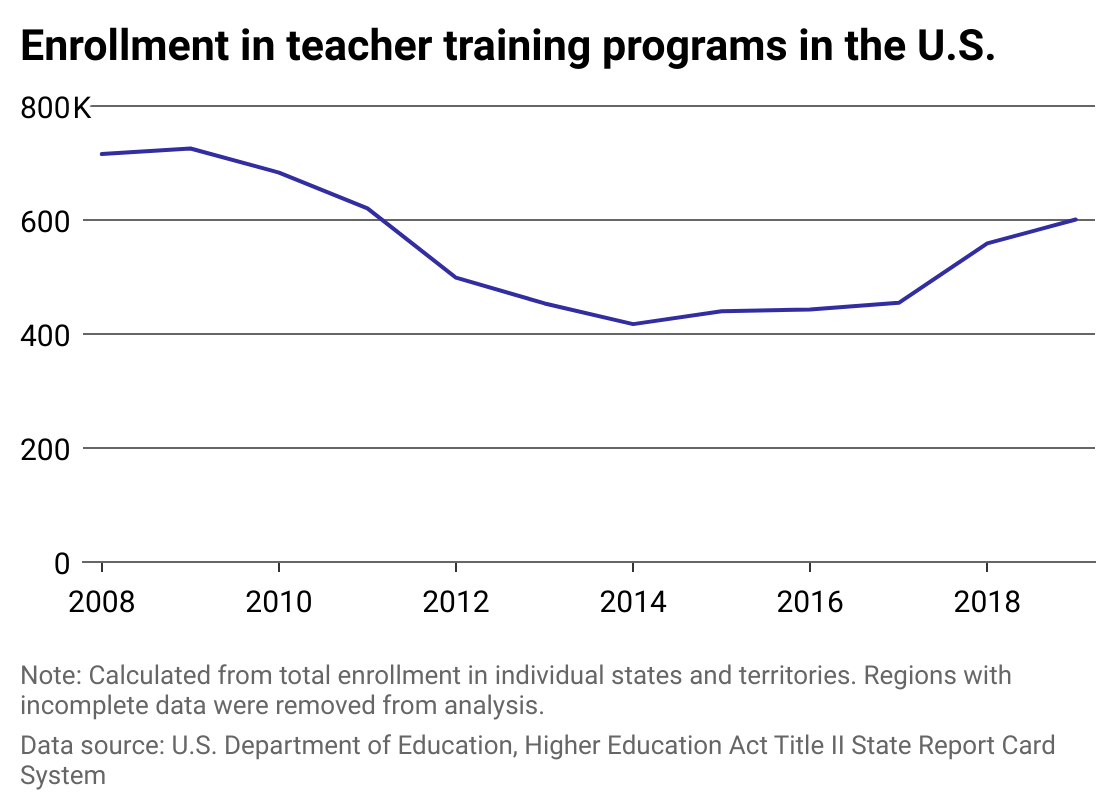

Leading up to the pandemic, enrollment in teacher preparation programs was starting to increase after a several-year decline

Line chart showing a decline in enrollment in teacher training programs since 2008 with a slight increase beginning in 2017

The number of undergraduate education degrees conferred each year remained stable until the early 2010s, when a gradual decline soon led to fewer than 90,000 bachelor’s degrees being awarded in the 2018-2019 school year. Tucked within that decline were even deeper reductions in degrees conferred in specialty subjects such as science, mathematics, and foreign languages.

Effects on the number of teachers employed soon reflected the decline in teaching degrees awarded. Between the 1999-2000 and the 2017-2018 school years, the number of full- and part-time public school teachers rose 18% to 3.5 million teachers, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. That figure broke down just about evenly at the elementary and secondary education levels. But by the 2019-2020 school year, the number of teachers fell to 3.2 million and by 2020-2021 to just over 3 million.

ESpark

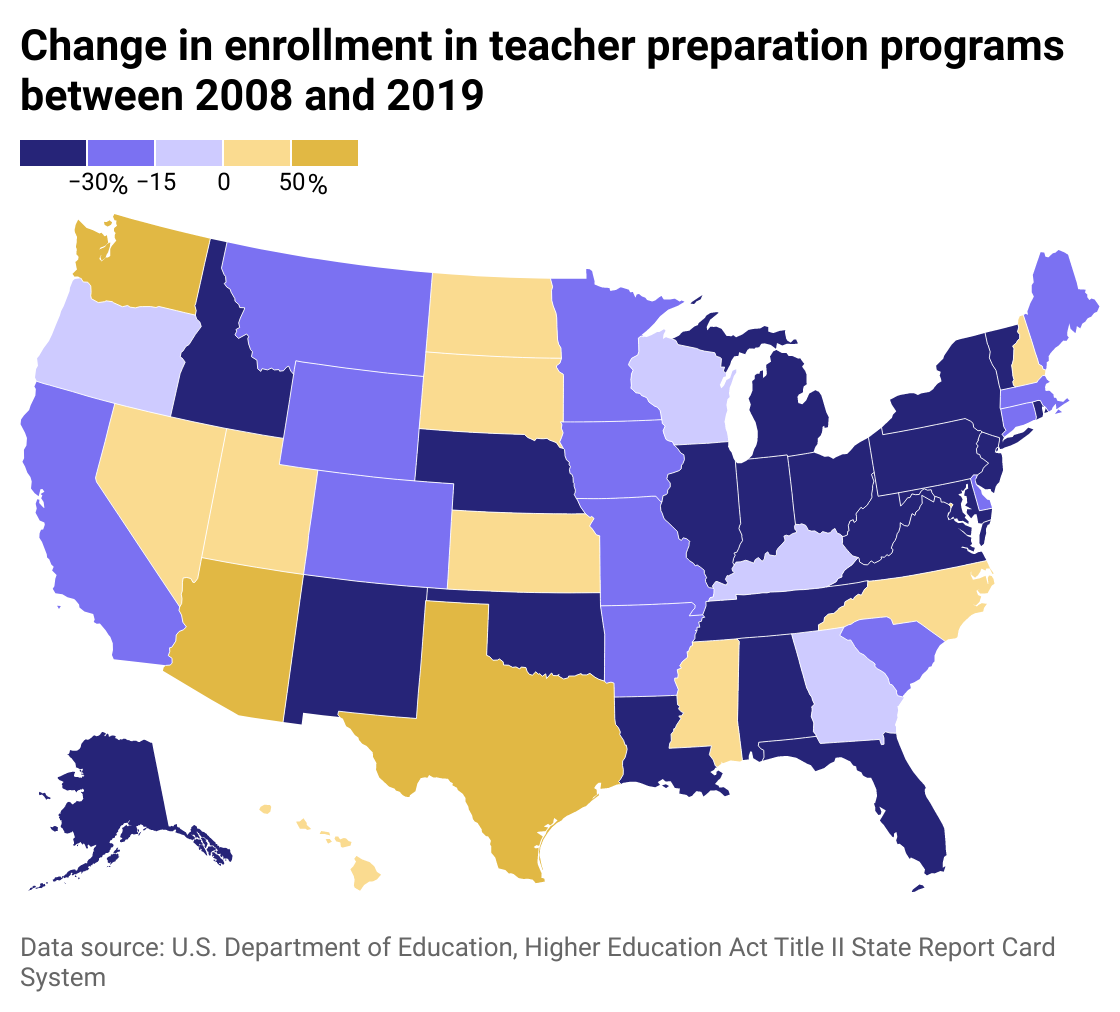

Most states have seen decreases in teacher education enrollment since 2008

State map showing that majority of states have seen declines in teacher training program enrollment since 2008

The number of students completing teacher education programs fell by more than one-third between 2008 and 2019, according to a 2022 report by the AACTE. The sharpest drops came in specialty subjects such as bilingual education, math, science, and special education. Changes in enrollment is one causative behind this drop. In the decade preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, most states saw moderate to more significant drops in students seeking teaching degrees. Particularly hard-hit were Midwestern and Rust Belt states, as well as seeming outliers such as Alaska and Florida, whose Department of Education outlined critical shortages in no fewer than eight subject areas going into the 2019-2020 school year.

The Center for American Progress reported some startling numbers the year before the coronavirus pandemic—a more than 50% drop in teacher education in nine states. The declines were 80% in Oklahoma, 67% in Michigan, 62% in Pennsylvania, 61% in Delaware, 60% in Illinois, 55% in Idaho, 54% in Indiana and New Mexico, and 51% in Rhode Island. Flat wages, heavy workloads, and the politicization of schools have been cited as some of the biggest influences behind these decreases.

ESpark

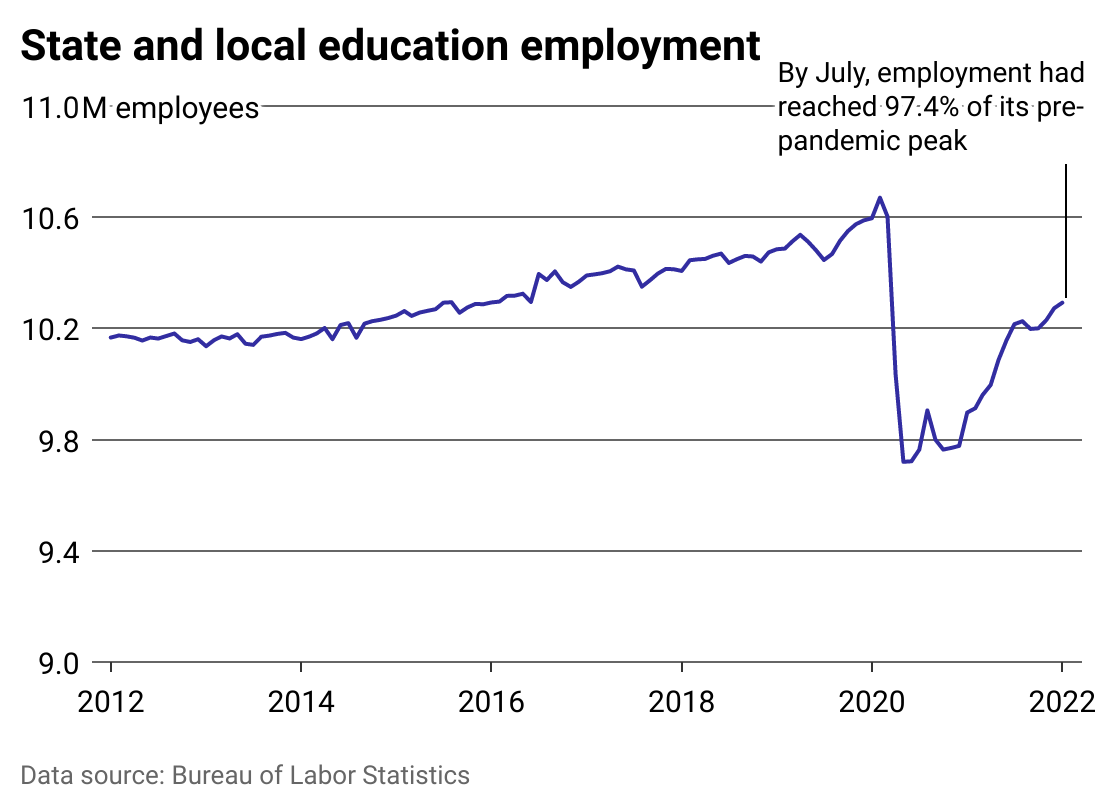

Employment levels haven’t returned to pre-pandemic numbers

Line chart showing local and state education employment is about 97% of the pre-pandemic peak

The drop in education employment resulting from the pandemic was the largest ever. However, it is not known exactly what jobs were lost and how many of those were teachers. A survey by the RAND Corporation discovered that 90% of school districts had changed operations in one or more schools during the 2021–2022 school year because of teacher shortages. It also found that more than three-quarters had increased their teaching and nonteaching staff to levels exceeding those before the pandemic. Additionally, one-quarter to one-third of districts had increased pay or benefits for bus drivers, relaxed hiring requirements for substitute teachers, and assigned staff to cafeteria duties.

ESpark

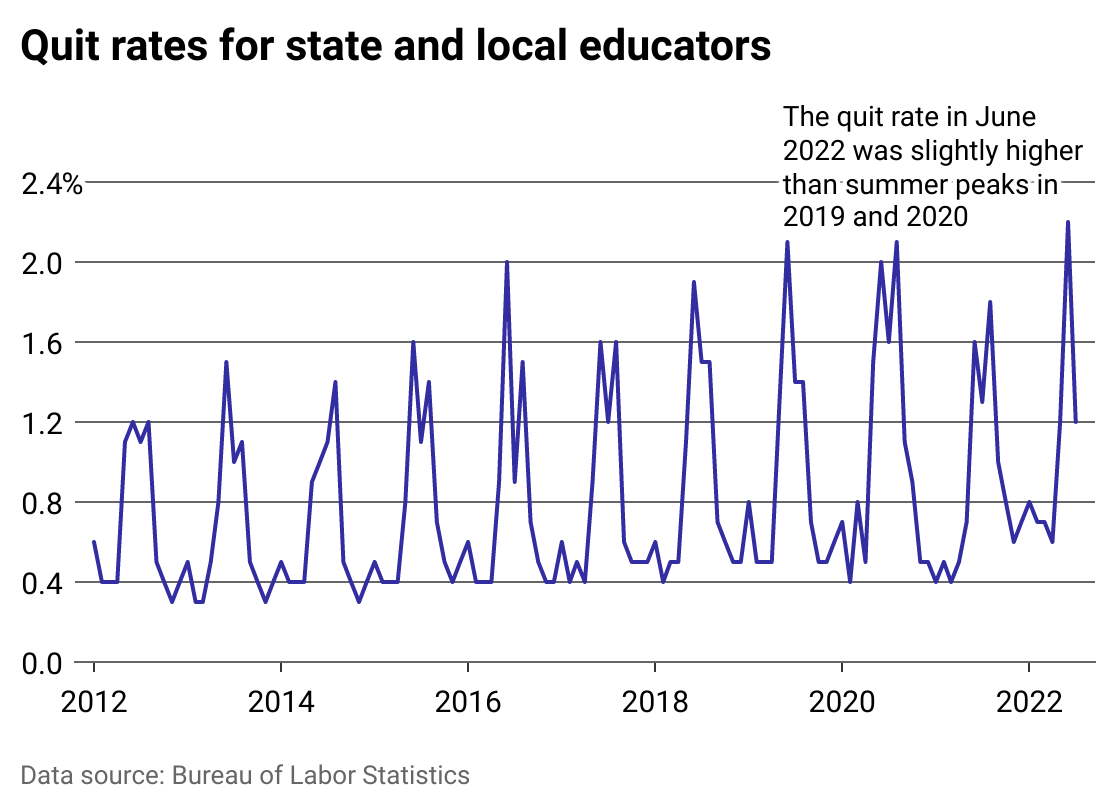

Summers have the highest quit rates for public educators, and June 2022 was a new peak

Line chart showing seasonal trends of state and local educator quit rates, with summers showing peaks

Summer months tend to be a time for reflection—the school year has come to a close and the accumulation of the academic year’s trials and stresses can be looked at more objectively—thus it is a period that sees teachers leaving the profession. (Though midyear quitting does occur, as well.) There are several reasons why a teacher might choose to leave the classroom, but the two most generally cited are burnout and inequitable earnings.

A Gallup poll released in June 2022 found that workers in K-12 schools reported the highest rates of burnout of any field in the country. More than four in 10 responded that they “always” or “very often” felt burned out at work. Workers at colleges and universities had the next highest level (35%). The National Education Association published figures in April 2022 showing the average teacher salary to be $66,397 for the 2021-2022 school year. When the salaries are adjusted for inflation, teachers are earning on average $2,179 less per year than they did a decade ago.

This story originally appeared on eSpark and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.