Broken US-Indigenous treaties: A timeline

MPI // Getty Images

Broken US-Indigenous treaties: A timeline

As long as the United States has negotiated treaties with Indigenous nations, it has broken those treaties. There is a popular tendency to think of these treaties as inanimate artifacts of the distant past. This belief, however, is a symptom of the historical amnesia that continues to relegate present-day Indigenous rights issues to the margins. Treaties are, in fact, living documents, which even today legally bind the United States to the promises it made to Native peoples centuries ago. Treaties also acknowledge the inherent sovereignty of Indigenous nations, a fact that has been disputed and undermined in U.S. courts and Congress since 1831, when the Supreme Court ruled that tribes were “domestic dependent nations” without self-determination.

Of the nearly 370 treaties negotiated between the U.S. and tribal leaders, Stacker has compiled a list of 15 broken treaties negotiated between 1777 and 1868 using news, archival documents, and Indigenous and governmental historical reports.

You may also like: Biggest Native American tribes in the U.S. today

![]()

Francis G. Mayer // Getty Images

Treaty With the Delawares/Treaty of Fort Pitt (1778)

The 1778 Treaty with the Delawares was the first treaty negotiated between the newly formed United States and an Indigenous nation. The Lenape (Delaware) were already being forced from their ancestral homelands in New York City, the lower Hudson Valley, and much of New Jersey when the Dutch settled there in the 17th century. The treaty stipulated peace between the Lenape and the U.S. as well as mutual support against the British. However, this supposed peace did not last long: In 1782, Pennsylvania militiamen murdered almost 100 Lenape citizens at Gnadenhutten, forcing the Lenape out toward Ohio.

Culture Club // Getty Images

Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1784)

Weakened by the constant encroachment of white settlers after the Revolutionary War, the Iroquois Confederacy was forced to cede part of New York and a large portion of present-day Pennsylvania in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. In return, the U.S. promised to protect tribal lands from further settlement by white colonists. In the following years, the U.S. did not enforce the treaty terms, and the lands inhabited by the Iroquois Confederacy continued to shrink.

Hulton Archive // Getty Images

Treaty of Hopewell (1785-86)

The Treaty of Hopewell includes three treaties signed by the U.S. and the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw Nations at General Andrew Pickens’ plantation following the Revolutionary War. The treaties supposedly offered the three tribes the protection and friendship of the U.S. and promised no future settlement on tribal lands. Despite these terms, the encroachment of white settlers onto treaty territory was already underway, and future treaties would shrink Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw lands even further.

Culture Club // Getty Images

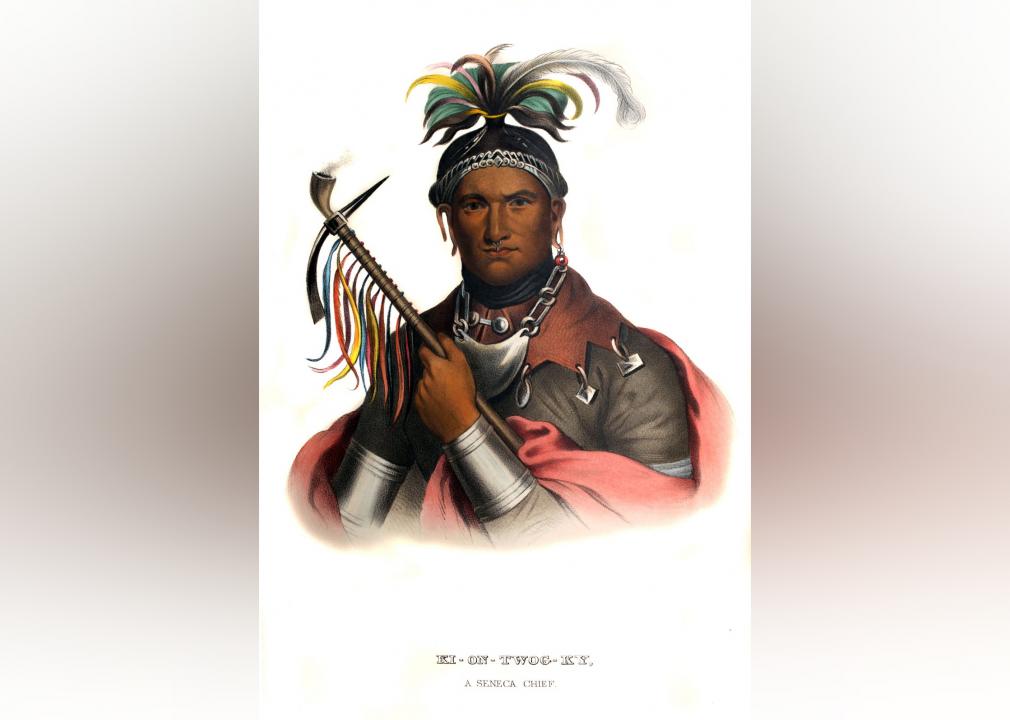

Treaty of Canandaigua/Pickering Treaty (1794)

In 1794, the U.S. government and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, or Six Nations (comprising the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca, and Tuscarora Nations of New York), signed the Treaty of Canandaigua. In exchange for the Confederacy’s allyship after the Revolutionary War, the U.S. returned over a million acres of Iroquois land that had been previously ceded in the Fort Stanwix Treaty. The Canandaigua Treaty also recognized the sovereignty of the Six Nations to govern themselves and set their own laws.

Despite this apparent act of friendship, the land returned to the Six Nations was lost to U.S. expansion, and the tribes were forced to relocate. While the Onondaga, Seneca, Tuscarora, and Oneida stayed on reservations in New York, the Mohawk and Cayuga moved into Canada.

Three Lions // Getty Images

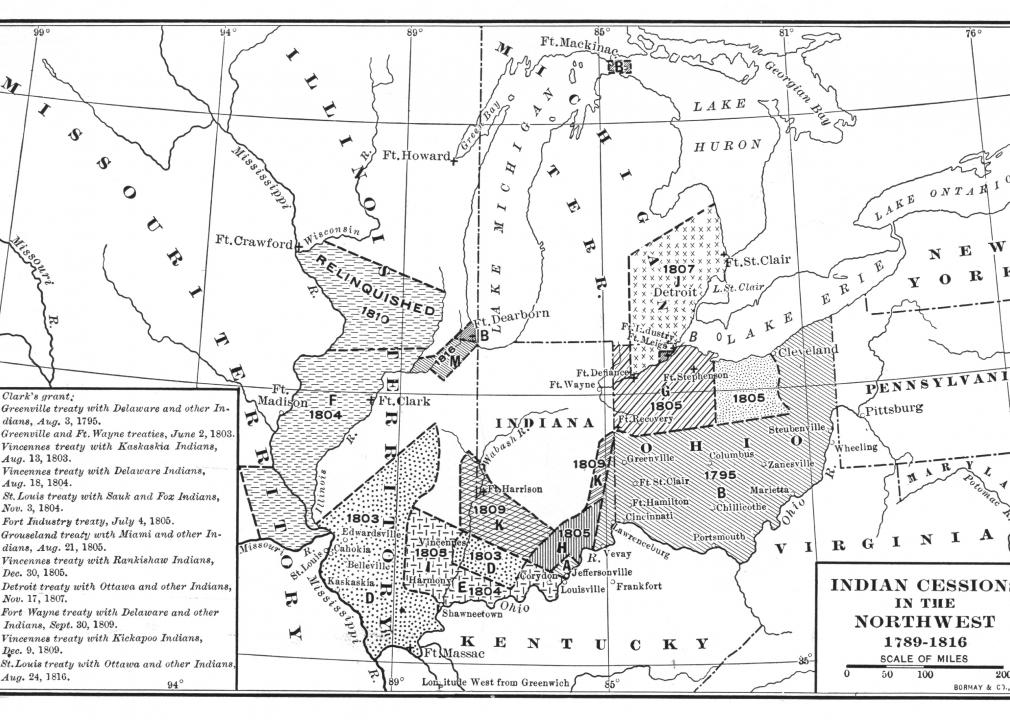

Treaty of Greenville (1795)

An increasing number of white settlers moved into the Great Lakes region in the 1780s, escalating tension with established Indigenous nations. The Shawnee, Delaware, Miami, Ottawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi Nations banded together as the Northwestern Confederacy and assembled an armed resistance to prevent further colonization.

In 1794, a large contingent of the U.S. military, led by General “Mad” Anthony Wayne, was tasked with putting an end to the Northwestern Confederacy’s resistance. The Confederacy was defeated in the Battle of Fallen Timbers and forced to sue for peace. The Treaty of Greenville saw the tribes of the Northwestern Confederacy cede large tracts of land in present-day Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Wisconsin, and Illinois. The treaty was soon broken, however, by white settlers who continued to expand their reach into treaty lands.

You may also like: Stories behind the Trail of Tears for every state it passed through

Hulton Archive // Getty Images

Treaty with the Sioux (1805)

In 1805, General Zebulon Pike mounted an expedition up the Mississippi River without informing the U.S. government. Pike met with a group of Dakota leaders, who allegedly ceded 100,000 acres of land to build a fort and promote U.S. trade in exchange for an unspecified amount of money. Of the seven Dakota leaders, only two signed the treaty. Though Pike valued the purchase at $200,000 in his journal, he left only $200 worth of gifts upon signing. The president never proclaimed the treaty, a necessary step that makes treaties official, and the U.S. adjusted the purchase price to $2,000.

Interim Archives // Getty Images

Treaty of Fort Wayne (1809)

In the Treaty of Fort Wayne, the Potawatomi, Delaware, Miami, and Eel River tribes ceded 2.5 million acres of their lands in present-day Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, and Ohio for roughly 2 cents an acre, under pressure from William Henry Harrison, the then-governor of Indiana. Not long after, Harrison led an attack on a camp of followers of Tenkswatawa, the Shawnee Prophet, and Tecumseh, who resisted the encroachment of white settlers on the Ohio Valley Nations. The violence spurred by this attack persisted into the War of 1812.

Kean Collection // Getty Images

Indian Removal Act (1830)

Though not technically a treaty, the Indian Removal Act of 1830 functioned as a displacement mechanism and was largely responsible for the treaties created over the following decades. President Andrew Jackson had long been a violent proponent of the forced relocation of Indigenous tribes from the southeast to western areas, leading military efforts against the Creek Nation in 1814 and negotiating many treaties which dispossessed tribes of their lands.

The Indian Removal Act created a process by which the president could exchange tribal lands in the eastern United States for federally designated land west of the Mississippi River by negotiating removal treaties with Indigenous nations. While the act was framed as a peaceful and voluntary process, tribes that did not “cooperate” were made to comply through military force, cheated or tricked out of their land, or subjected to the violence of local white settlers.

CarolineJQ // Wikimedia Commons

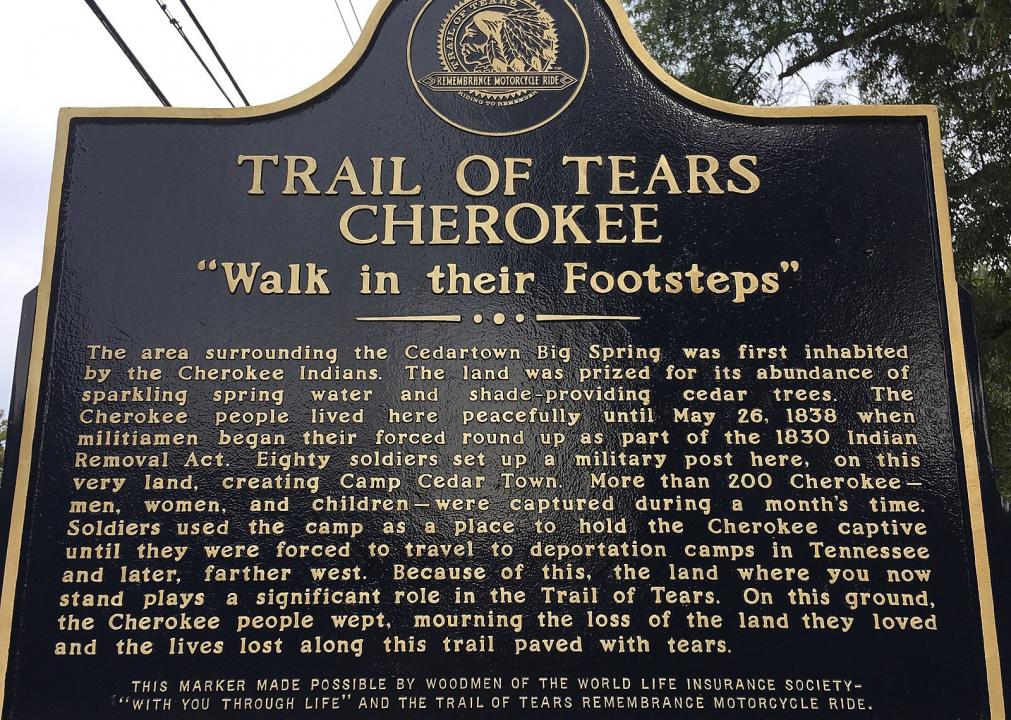

Treaty of New Echota (1835)

Following the passage of the Indian Removal Act, facing tremendous pressure to move west, a small group of Cherokees not authorized to act on behalf of the Cherokee people negotiated the Treaty of New Echota. The treaty gave up all Cherokee lands east of the Mississippi River in exchange for $5 million and new territory in Oklahoma. Even though most Cherokee people considered the agreement fraudulent, and the Cherokee National Council formally rejected it in 1836, Congress ratified the treaty.

Two years later, the Treaty of New Echota was used to justify the forced removal of the Cherokee people. In 1838, roughly 16,000 Cherokees were rounded up by the U.S. military and forced to march 5,043 miles to their new lands. Over 4,000 Cherokee people died on the Trail of Tears.

Chris Light // Wikimedia Commons

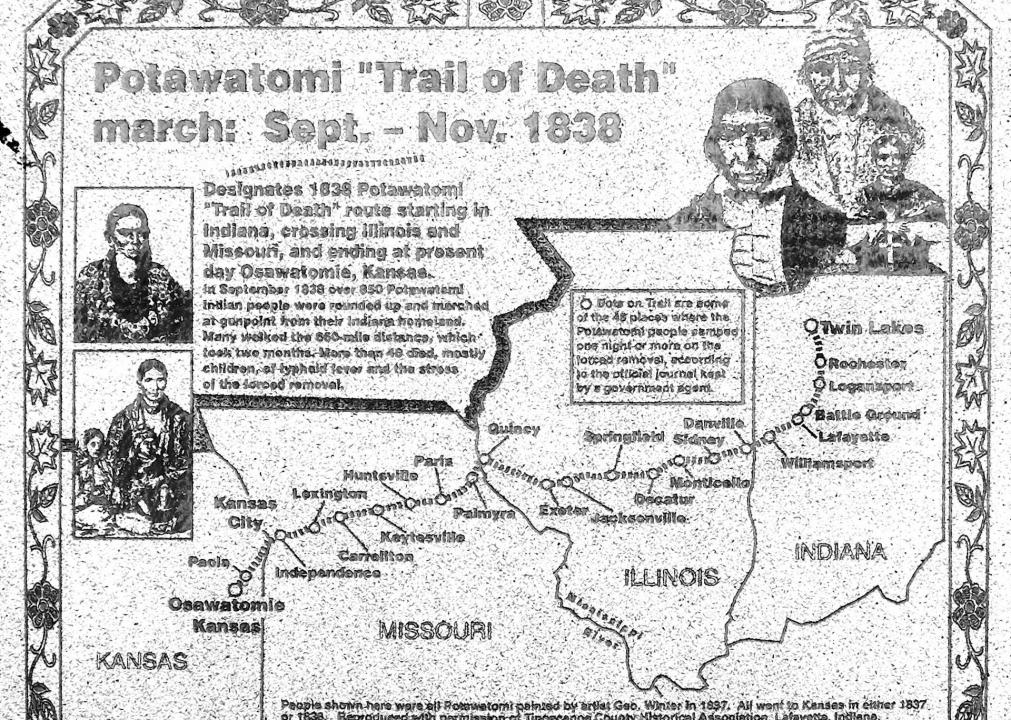

Treaty with the Potawatomi (1836)

In 1832, the Potawatomi Nation signed a peace treaty with the U.S. ensuring the Potawatomi people’s safety on their reservations in Indiana. Still, it wasn’t long before the U.S. broke this treaty. Further negotiations followed, but in 1836, the Potawatomi were forced to sell their land for around $14,000 and move westward. Though many Potawatomi tried to stay, in 1938, the U.S. government enforced their removal by way of a 660-mile forced march from Indiana to Kansas. Of the 859 Potawatomi people who began what would later be known as the Trail of Death, 40 died, many of whom were children.

You may also like: 20 influential Indigenous Americans you might not know about

MPI // Getty Images

Fort Laramie Treaty (1851)

The 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty “defined” the territory of the Great Sioux Nation (Dakotas, Lakotas, and Nakotas) in North and South Dakota, Nebraska, Wyoming, and Montana, in exchange for the creation of roads and railways and the promise of the U.S. to protect the Sioux from American citizens. Nevertheless, settlers and the U.S. military violated the treaty and invaded Lakota lands. Disputes over the treaty’s integrity persist, as evidenced by the building of the Dakota Access Pipeline, which was constructed on treaty lands near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. In 2016, water protectors and activists established a camp at Standing Rock to prevent the pipeline’s construction, where they were subjected to attack dogs and other methods of excessive force by law enforcement. The pipeline is still operational.

ullstein bild Dtl. // Getty Images

Treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota (1851)

Under threat of military violence from the increasing numbers of white settler-colonists moving into Minnesota, the Dakota and Mendota were forced to cede millions of acres of land in the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota in exchange for reservations and $1,665,000—the equivalent of about 7.5 cents per acre. However, the Dakota and Mendota never received either provision. The representatives from the U.S. government who negotiated the treaty tricked the Dakota representatives into signing a third document, which reallocated the funds meant for the Dakota and Mendota to traders to fulfill invented “debts.” The U.S. Senate further violated the treaty by eliminating the provision for reservations.

Hulton Archive // Getty Images

Land Cession Treaty with the Ojibwe/Treaty of Washington (1855)

In the 1855 Treaty of Washington, the Ojibwe ceded nearly all of their remaining land not already lost to the U.S. during previous treaties. This new treaty also created the Leech Lake and Mille Lacs Reservations and allotted reservation land to individual families. In doing so, the U.S. attempted to subvert the Ojibwe’s traditional relationship with the land by instating a system of private property, as well as forcing the Ojibwe people to become farmers, a departure from their historical lifestyle of hunting, fishing, and gathering. However, it was mutually agreed that the Ojibwe would be able to continue hunting and fishing on ceded territory.

Unfortunately, in the decades following the signing of the treaty, the state of Minnesota outlawed hunting and harvesting without a license on off-reservation land, a direct violation of the treaty. Despite the Supreme Court’s reaffirmation of the Ojibwe’s hunting and gathering rights on ancestral lands in 1999, conflicts over the use of these lands, including for pipeline development, are ongoing.

Kean Collection // Getty Images

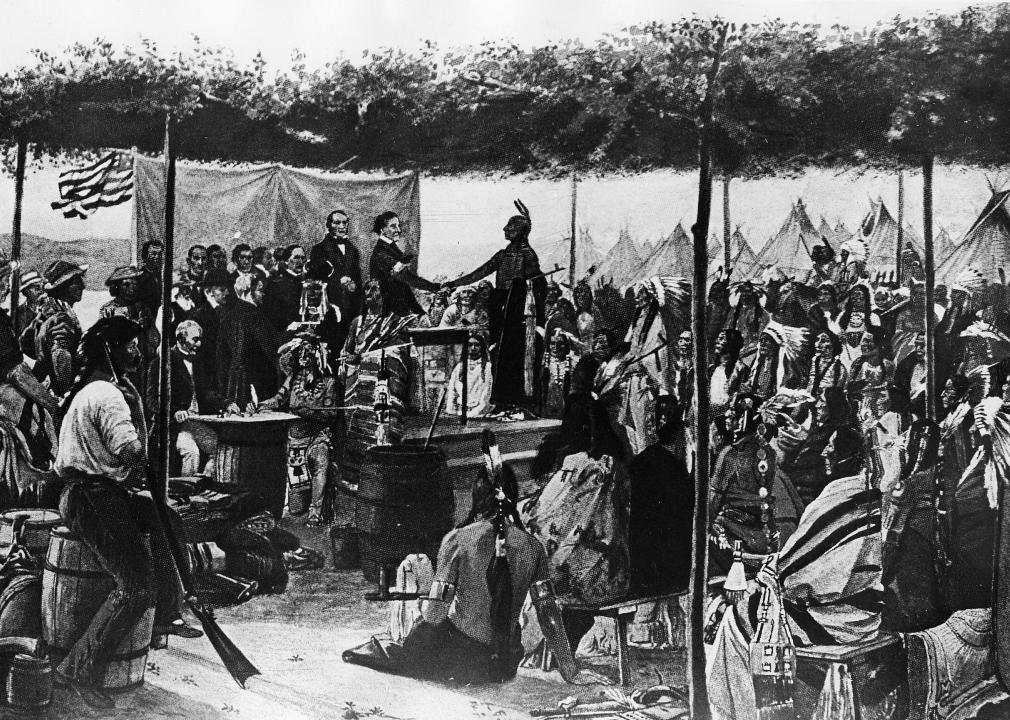

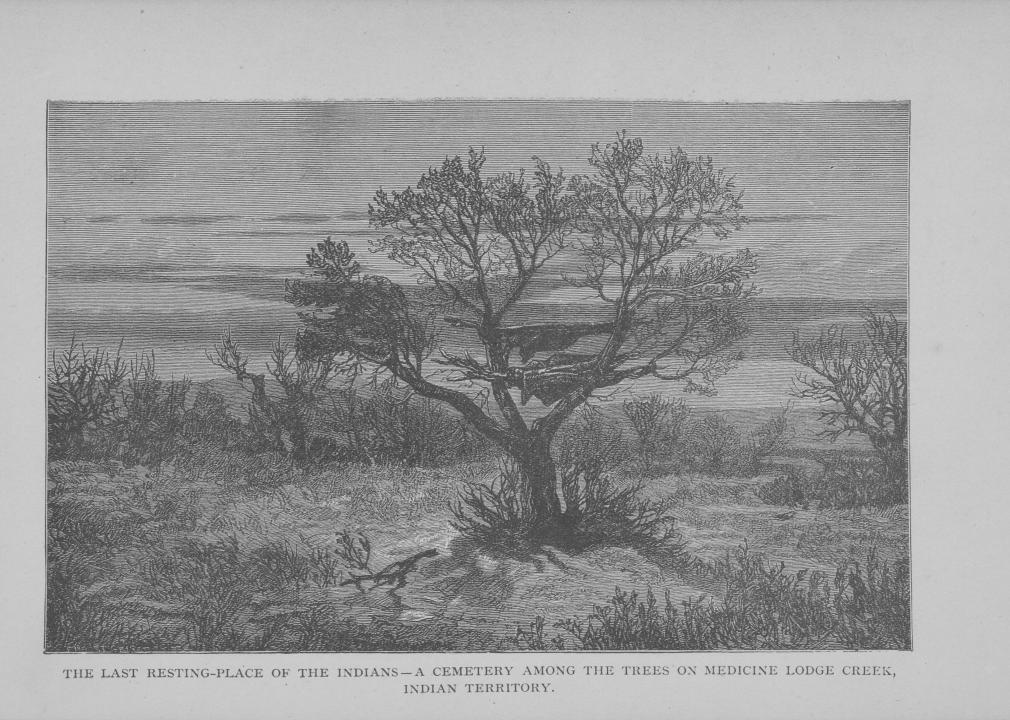

Medicine Lodge Treaty (1867)

Two years after the culmination of the Civil War, violence against Plains tribes instigated by westward-moving white settlers came to a head. More than 5,000 representatives of the Kiowa, Comanche, Arapaho, Kiowa-Apache, and Southern Cheyenne nations met with U.S. government delegates to ostensibly negotiate peace. Ultimately, the treaty relocated the Comanches and Kiowas onto one reservation and the Cheyennes and Arapahoes onto another. Even though the participating tribes never approved the treaty, Congress ratified it in 1868 and then quickly began violating the terms, withholding payments, preventing hunting, and cutting down the size of reservations.

In 1903, Kiowa chief Lone Wolf sued the U.S. for defrauding the tribes who participated in the Medicine Lodge Treaty. In a devastating ruling that would have grave consequences for Indigenous land rights, the Supreme Court ruled that Congress could legally “abrogate the provisions of an Indian treaty.” In other words, any treaty made between the U.S. and Native American tribes could be broken by Congress, rendering treaties essentially powerless.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Fort Laramie Treaty (1868)

The Fort Laramie Treaty was negotiated with the Sioux (Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota Nations) and the Arapaho Tribe. It established the Great Sioux Reservation, which comprised all of the South Dakota west of the Missouri River, and protected the sacred Black Hills, designating the area as “unceded Indian Territory.” It only took until 1874 for the U.S. to violate the terms of the treaty when gold was discovered in the Black Hills. The boundaries outlined in the treaty were hastily redrawn to allow white Americans to mine the area.

In the 1980 case United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians, the Supreme Court ruled that the U.S. had illegally expropriated the Black Hills, and that the Sioux were entitled to over $100 million in reparations. The Sioux turned down the money, saying that the land had never been for sale. Conflicts over the U.S.’s illegal usage of Sioux lands outlined in the Fort Laramie Treaty are ongoing. In 2018, the Rosebud Sioux Tribe and the Fort Belknap Indian Community sued the Trump administration for violations concerning the permitting of the Keystone XL Pipeline, which was shut down in June 2021.

You may also like: A history of police violence in America