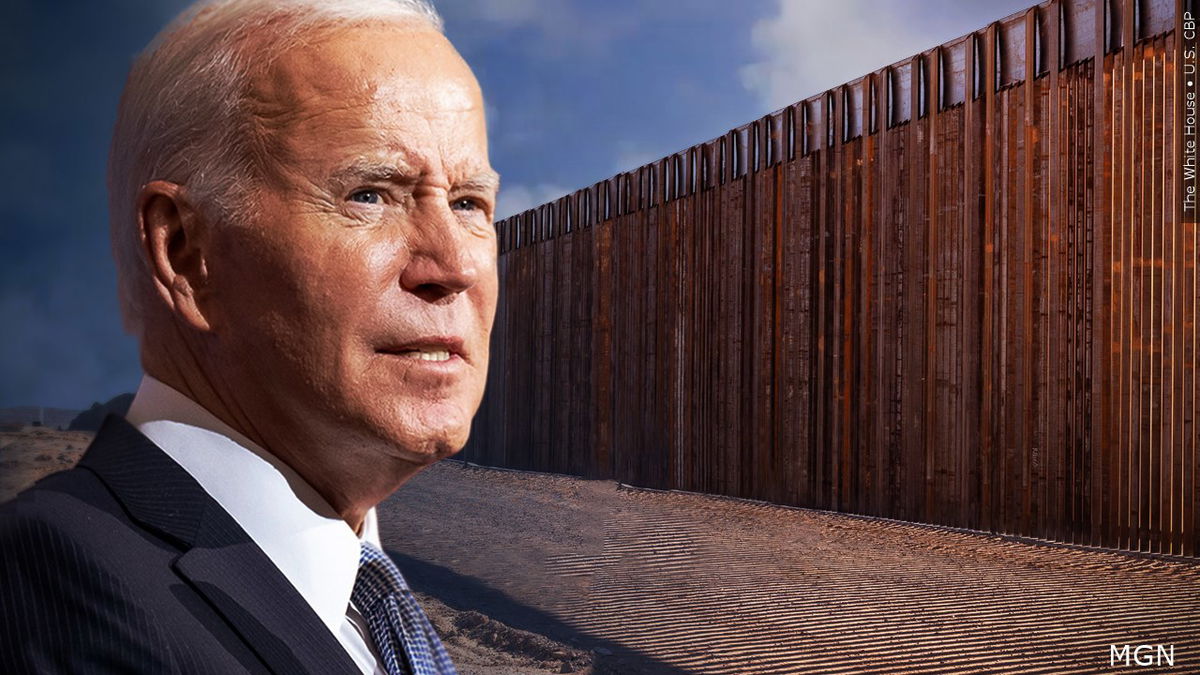

US to limit asylum at Mexico border, open 100 migration hubs

By REBECCA SANTANA, COLLEEN LONG and MORGAN LEE

WASHINGTON (AP) - President Joe Biden's administration this week will begin denying asylum to migrants who show up at the U.S.-Mexico border without first applying online or seeking protection in a country they passed through.

It's part of new measures meant to crack down on illegal border crossings while creating new legal pathways, including a plan to open 100 regional migration hubs across the Western Hemisphere, administration officials said.

While stopping short of a total ban, the measure imposes severe limitations on asylum for those crossing illegally who didn't first seek a legal pathway. The rule was first announced in February and is being finalized Wednesday, the officials said. It’s almost certain to face legal challenges. In 2019, then-President Donald Trump pursued similar but stricter measures, but a federal appeals court prevented them from taking effect.

U.S. officials also said they had plans to open regional hubs around the hemisphere, where migrants could apply to go to the U.S., Canada or Spain. Two hubs were previously announced in Guatemala and Colombia. It's unclear where the other locations would be. The administration officials spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss ongoing border plans that were not yet public.

The measures are all meant to fundamentally alter how migrants go to the U.S. southern border. Coronavirus pandemic-related restrictions that are ending this week had allowed border officials to quickly return people — and they did so 2.8 million times. But even as the restrictions, known as Title 42, were in effect, border crossings rose to all-time highs. Congress has failed to make any major immigration law changes in decades.

U.S. officials are bracing for large numbers of migrants who may try to cross the border this week, possibly to circumvent the new rules that take effect Thursday. Others were waiting until after Title 42 goes away, thinking their chances might be better. Once the change happens, migrants caught crossing illegally will not be allowed to return for five years, and they can face criminal prosecution if they do.

Roughly 24,000 law enforcement officers were stationed along the 1,951-mile (3,140-kilometer) border with Mexico. An additional 1,500 active-duty military troops are being sent to back up U.S. Customs and Border Protection but will not interact with migrants. And 2,500 National Guard troops are already there, tasked to help out CBP.

Biden said Tuesday his administration was working to make the change orderly. “But it remains to be seen,” he told reporters. “It’s going to be chaotic for a while.”

The Democratic administration will return migrants from Haiti, Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua to Mexico if they do not apply online, have a sponsor and pass a background check. It will admit 30,000 per month from those nations to the U.S. with legal papers to work for two years. Mexico will continue to take back the same number who cross illegally.

In the Mexican border city of Reynosa, across from McAllen, Texas, groups on Tuesday handed out flyers that explained in English and Haitian Creole how to register for the CBP One app, which the U.S. has been using to allow migrants to schedule an appointment to try to gain admittance. Authorities plan to increase the number of appointments amid widespread frustration, and they're prioritizing people who have been waiting longest for appointments.

Standing in Reynosa’s central square, Haitian migrant Phanord Renel said he would not risk deportation to cross. “We don’t want to go back there (Haiti) because the situation is very complicated there,” he said. “If we can’t cross, we have to put up with it here. Maybe the government will do something for us. But cross illegally — no.”

Immigration officials are also planning to deploy as many as 1,000 asylum officers to conduct expedited screenings for asylum seekers to more quickly determine whether someone meets the standard to stay in the U.S.

Most of the people going to the U.S.-Mexico border illegally are fleeing persecution or poverty in their home countries. They ask for asylum and have generally been allowed into the U.S. to wait out their cases. That process can take years under a badly strained immigration court system, and it has prompted increasing numbers to go to the border hoping to get into the U.S.

Even though many ask for asylum, the legal pathway is narrow, and most do not meet the standard.

Authorities have spent months setting up interview rooms and phone lines at facilities along the border to facilitate screenings, part of a broad effort to expand the use of expedited removal proceedings aimed at migrants who forgo legal pathways to come to the U.S.

Officials acknowledged that reassigning asylum officers to the border will postpone routine asylum proceedings across much of the U.S. for weeks.