Arizona’s lack of mental health care providers underscored as COVID-19 increases depression, anxiety

By Allison Engstrom

Cronkite News

PHOENIX – Arizona ranks close to last in the nation when it comes to available mental health care providers – a problem that’s been underscored during a pandemic that is increasing anxiety and depression.

Heather Ross, a clinical assistant professor at Arizona State University who advises Phoenix Mayor Kate Gallego on health policy issues, said the state also lacks sufficient beds and inpatient facilities to treat patients with mental health challenges.

Still, she added: “You can build a building, you can stick a bed in a room, but unless you have the professionals to deliver the care, those beds almost don’t matter.”

Arizona ranks 47th among all 50 states and the District of Columbia in the rate of available mental health care providers, according to the latest report by the nonprofit group Mental Health America. The state’s ratio of 790 people for every 1 provider compares with Massachusetts’ leading rate of 180 to 1.

Providers include psychiatrists, psychologists, licensed clinical social workers, counselors, marriage and family therapists, and advanced practice nurses specializing in mental health care.

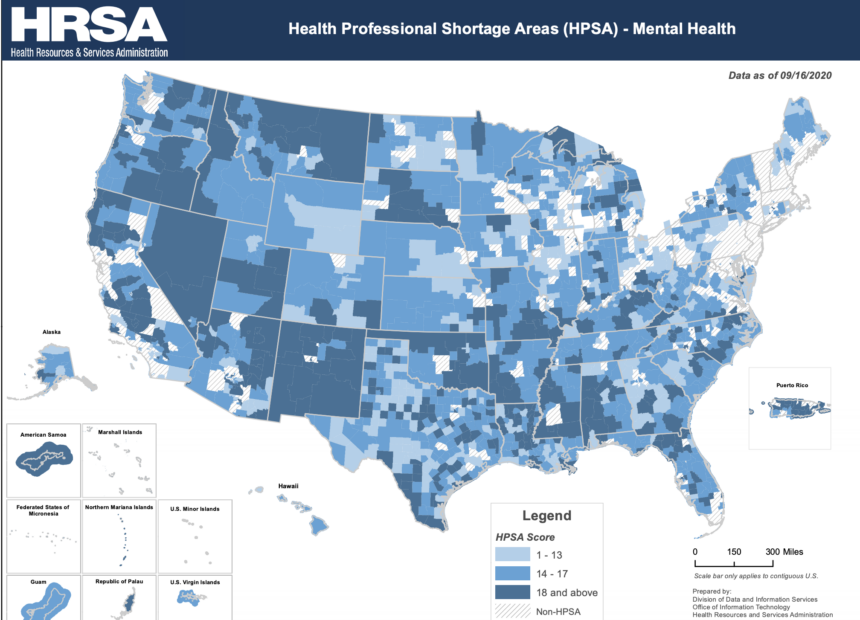

All 15 counties in Arizona include places considered Health Professional Shortage Areas specifically for mental health, according to data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The Navajo Nation is ranked as one of the highest areas of need. A 2017 study by Northern Arizona University’s Center for Health Equity Research found that the ratio of people to mental health providers in Navajo County, which includes a section of the Navajo reservation, was a whopping 1,504:1.

These provider shortages are especially concerning given the job losses, isolation and grief people are experiencing during the COVID-19 pandemic, Ross said. The Navajo Nation has been hit hard by the deadly disease, with more than 10,000 cases and 550 deaths, while statewide cases have surpassed 200,000, with more than 5,600 deaths.

Ross said it’s vital the dearth of behavioral health providers is addressed, because a mental health problem can affect every aspect of one’s life.

“It’s not like when you sprain your elbow and you can wear a sling,” she said. “You can’t put a Band-Aid on it and put it aside. It’s always with you.

“In a perfect world, every person who was experiencing mental illness, behavioral disorders or crisis would reach out … and would have a mental health professional immediately available.”

A June survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention documented how COVID-19 has increased mental health problems, particularly in younger adults, people of color, essential workers and unpaid adult caregivers. These groups have reported experiencing worse mental health, increased substance use and elevated suicidal ideation.

One organization trying to help is Flagstaff’s Stronger as One, a collaborative effort among several Coconino County organizations to create a culture of knowledge, compassion and action around mental health and well-being.

The group offers mental health first-aid training to identify, understand and respond to mental health crises or substance abuse issues.

Although not a replacement for the help of a licensed professional, those trained can serve as a first stopping point for people who need care, especially in areas where providers are limited.

“We’re working to normalize talking about it and make people aware of the regional resources that are there,” said Erica Shaw, Stronger as One program manager.

In partnership with the Arizona Department of Education, about 65 people in northern Arizona have been trained to date, Shaw said.

A bill to provide financial aid to students who commit to enter the mental health care workforce was introduced during the 2020 Arizona legislative session but didn’t make it out of committee.

The bill would have expanded the Arizona Teachers Academy program to provide scholarships ranging from $3,000 to $10,000 a year for students who agree to become social workers or counselors in Arizona public schools.

The measure’s sponsor, Sen. Sean Bowie, D-Phoenix, told Cronkite News he plans to reintroduce the proposal when the new legislative session begins in January.

Mental health conditions have worsened since the pandemic was declared in March, but even before then, reports of anxiety and depression had been on a “scary but steady increase,” said Mark Carroll, chief medical officer of Health Choice Arizona in Flagstaff.

Now, with some of the financial impacts of COVID-19, people may be putting their mental health on the back burner.

“If I don’t have stable housing or I don’t have money for reliable and consistent food on my table,” Carroll said, “other things are just not going to be a priority for me and it’s going to impact my health in general. And it’s going to have a significant impact on my mental health and well-being.”

Health Choice Arizona provides health coverage to over 200,000 people across Apache, Coconino, Maricopa, Mohave, Navajo, Gila, Yavapai and Pinal counties.

The 2017 NAU study noted that access alone isn’t the only barrier to getting mental health treatment. Stigma and cultural differences also play a role. Some respondents living in smaller communities said they feared the risk of being recognized when seeking care.

Historical trauma among Native Americans also can lead to a deep sense of hopelessness, the study found.

“Each different culture has a different way of approaching wellness and well-being and overall mental health. You can’t overlook that,” Shaw said. “You have to respect their cultural history … and meet them where they are.”

Shaw hopes to see the momentum of change and sharing of resources continue, especially as the pandemic goes on.

“We have this tendency to say, ‘Suck it up, brush it off, it’s no big deal, just snap out of it.’ But you don’t tell someone with cancer to snap out of it. So there’s this fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of mental health,” Shaw said.

“Ultimately, our mission is to build a culture of knowledge, compassion and action for mental health and well-being, so that we can all live better, healthier lives – together.”