A history of police violence in America

CHANDAN KHANNA/AFP via Getty Images

A history of police violence in America

Former police officer Derek Chauvin in April 2021 was found guilty of murdering George Floyd on May 25, 2020, when Chauvin knelt on the man’s neck for 9 minutes and 29 seconds while Floyd was in police custody. Floyd’s death touched off months of Black Lives Matters protests against police violence in general and disproportionate police violence against Black Americans in particular.

Those protests were frequently met with militarized police. Law enforcement utilized tear gas, pepper spray, rubber bullets, and batons in response to activities including a violin vigil for Elijah McClain; walking on the sidewalk in Buffalo, New York, during a daytime protest; and standing on porches in Minneapolis in the days following the murder of George Floyd. Protests and demands for change, including defunding the police, have continued, as have police killing American citizens.

Police killed 1,127 people in 2020 alone, according to Mapping Police Violence (MPV), and as of Oct. 6, police have killed nearly 800 people in 2021. Despite making up only 13% of the American population, Black people were 28% of the people killed by law enforcement that year. MPV statistics show that Black people are three times more likely to be killed by a policeman, despite being 1.3 times more likely to be unarmed. Black lives are being taken in stark numbers, but almost 99% of killings by police have not resulted in criminal charges, according to MPV.

Stacker compiled a list of 50 chronological events showing the history of police violence in the United States. This report highlights policies, organizations, and events, and explore how they relate to police brutality, institutionalized discrimination, and the loss of lives. Our research is based on news articles, government reports, and historical documentation including primary sources. Multiple methods that encourage racial division within the system have been enforced and continue to show up in statistics over the years.

From the beginning, discrimination was institutionalized in political and economic spaces. The need to inflict forced labor on Black lives after slavery was the main objective for the original police force in the South. This is where force was ingrained into police tactics, as hate groups such as the Ku Klux Klan merged with the system. Generation after generation, new rules were put into place specifically to target the Black population, including segregation, incarceration, voter suppression, redlining and lack of government assistance, and economic infrastructure. Statistically, in reported incidents alone, Black people’s experiences with the criminal justice system have always been vastly different from those of other groups.

Keep reading to learn more about the history of police violence in America, from 18th-century slave patrols in South Carolina to calls for defunding the police.

You may also like: Defining historical moments from the year you were born

![]()

AEsquibel23 // Wikimedia Commons

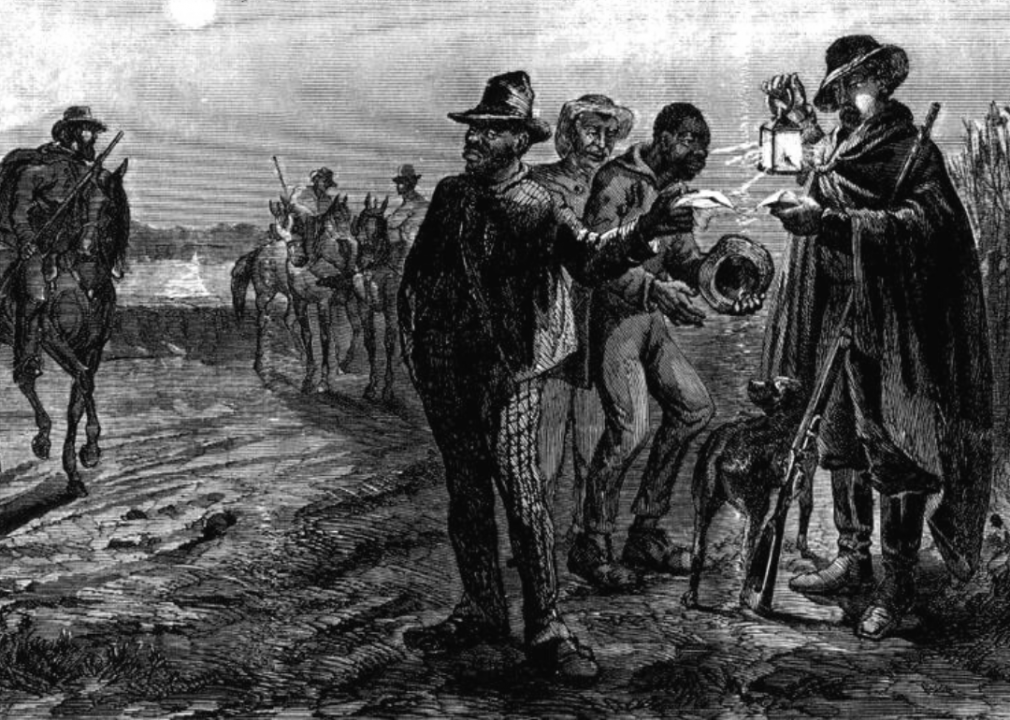

1704: Start of slave patrols in South Carolina

In an effort to mandate their power over African slaves, government leaders in Charleston, South Carolina, created the first slave patrol, birthing law enforcement as we know it. Not shy to commit acts of terror or violence, the “patrollers,” as these slave patrols were called, took on the responsibilities of chasing down slaves on horseback and returning them to slavery, embedding racism into the system.

[Pictured: Depiction of a slave patrol.]

Corbis // Getty Images

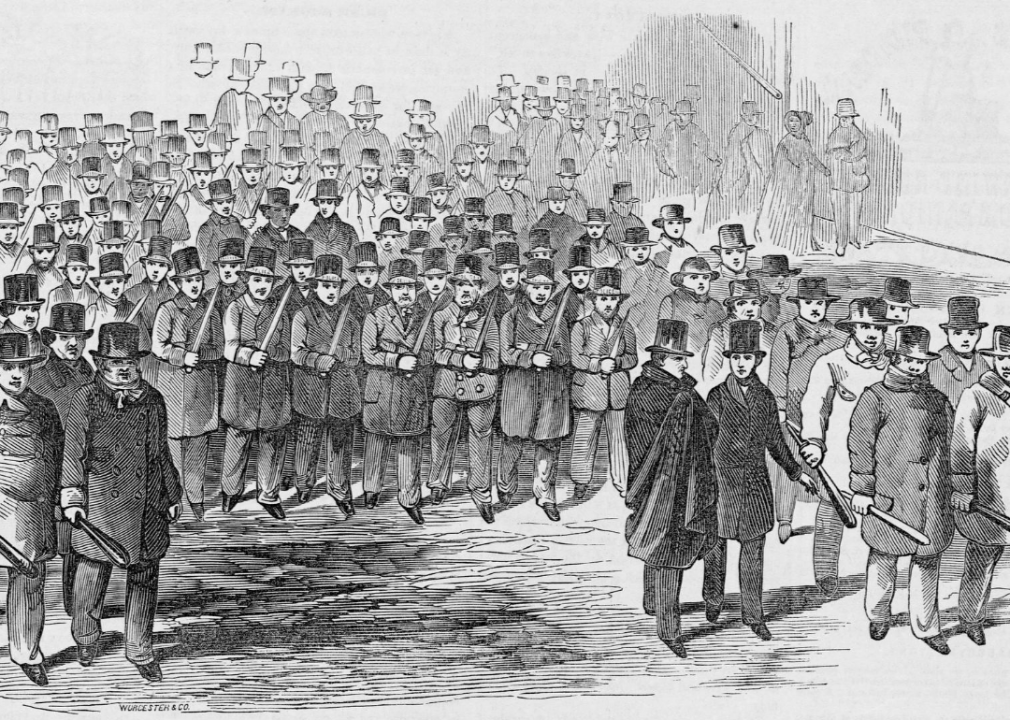

1838: First police department

The first official American police department was established in Boston in 1838 after lighter methods of policing failed. While policing systems in the South centered on the slave system, the North policed labor unions targeting Eastern European immigrants. As Black people fled the horrors of the Jim Crow South, they too became the victims of brutal and punitive policing in the Northern cities where they sought refuge.

[Pictured: The mayor of Boston and police marshal Francis Tukey lead the procession of fugitive slave Thomas Sims as they move him to the docks for extradition to Georgia.]

Hulton Archive // Getty Images

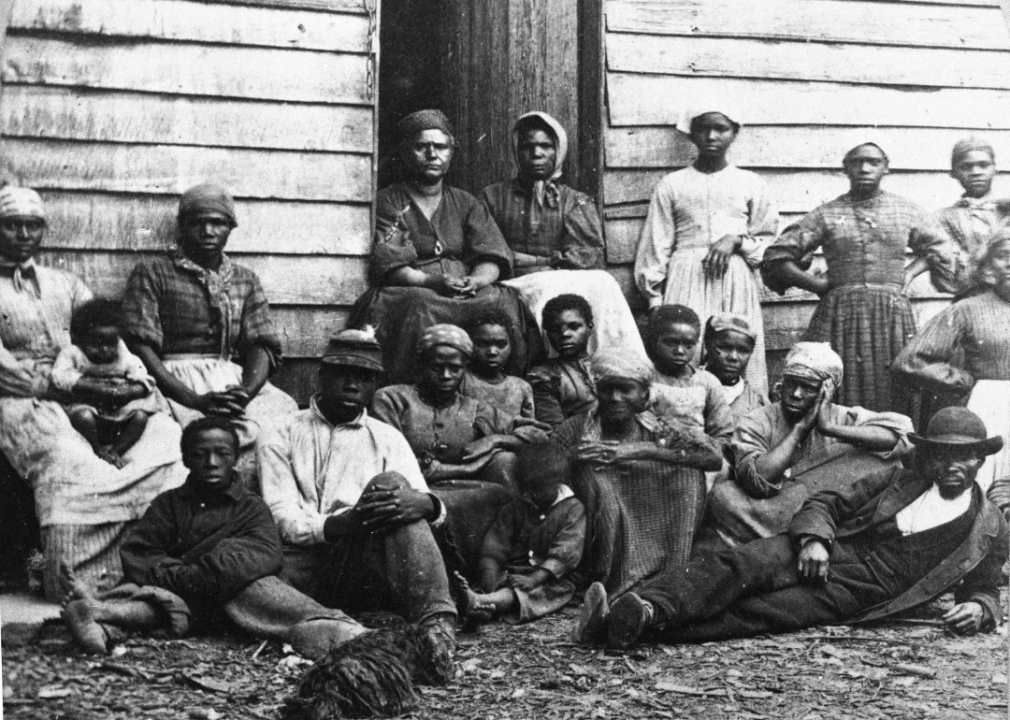

1865: Southern states establish first ‘black codes’

Slavery was officially abolished in America by law after the Civil War, but former slaves were far from free. African Americans were heavily policed following emancipation by both law enforcement and government officials who institutionalized racism with slavery by a new name: Black codes. These were a set of laws designated for Black people and newly freed slaves that restricted property ownership, forced cheap labor, and perpetuated other racist behaviors. The Black codes were precursors to Jim Crow laws, which lasted late into the 20th century.

[Pictured: Fugitive slaves who were emancipated upon reaching the North, circa 1865.]

Universal History Archive // Getty Images

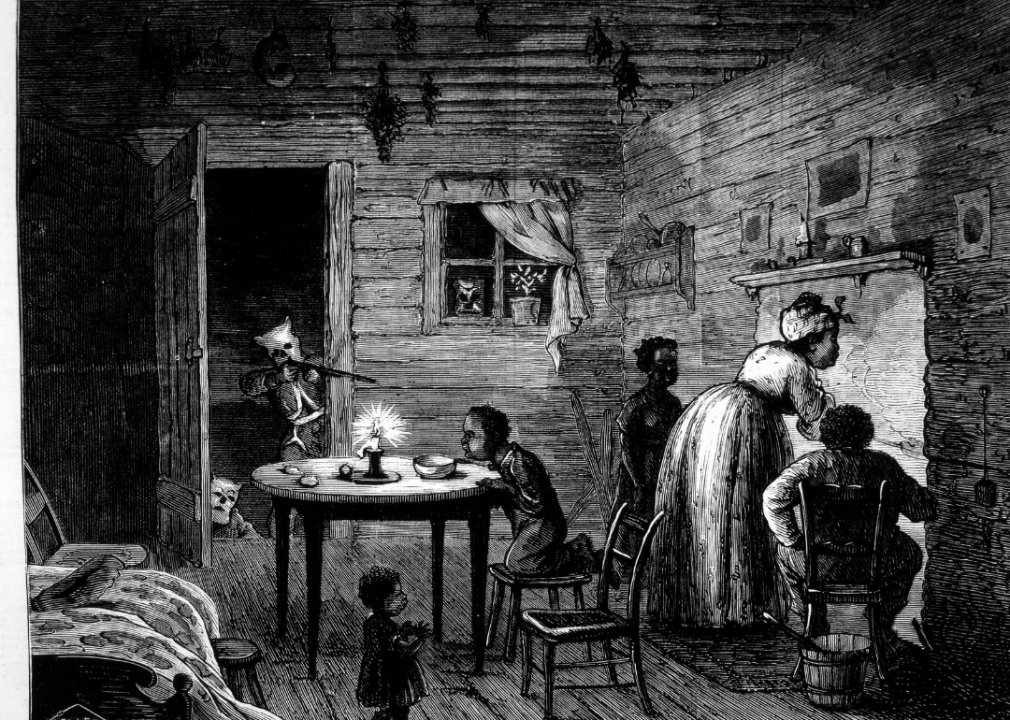

Dec. 24, 1865: Ku Klux Klan formed

Threatened by the newly earned liberation of freed slaves, the Ku Klux Klan and other hate groups were formed as acts of power by white citizens—and often former slave traders. Using white supremacy as motivation, these groups regularly terrorized Black communities, carrying out lynchings and destroying Black property. Soon, KKK members began joining law enforcement and other government positions, especially in the South.

[Pictured: “Visit of the Ku-Klux,” wood engraving, Harper’s Weekly, Feb. 24, 1872.]

Corbis // Getty Images

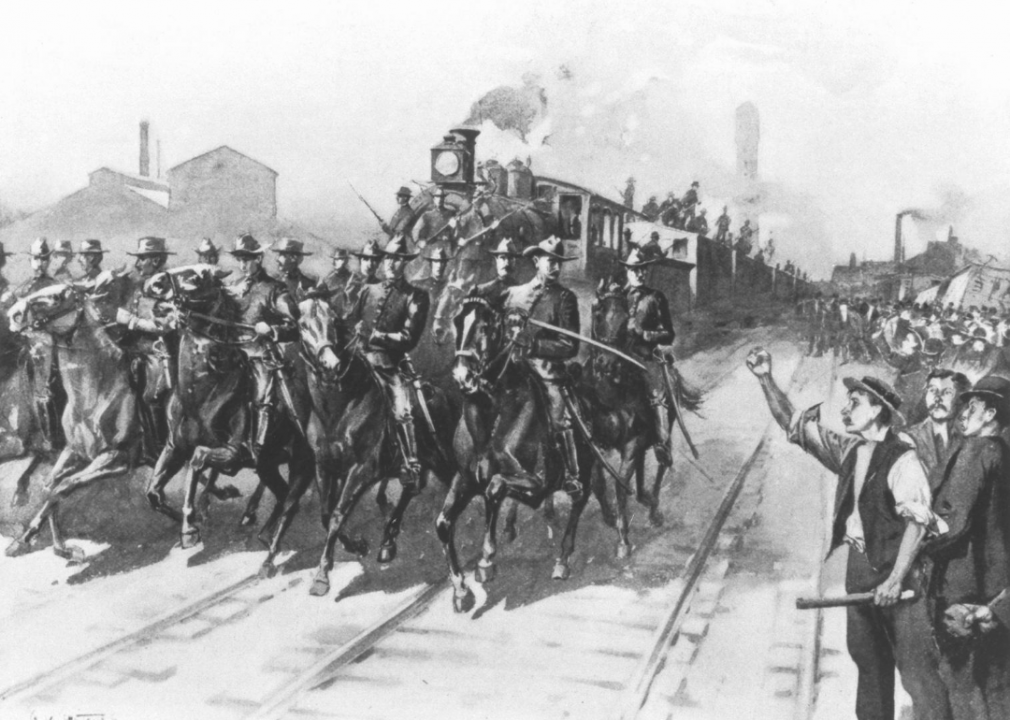

1877: Protesters and law enforcement clash in the Great Railroad Strike

Railroad workers dismayed by pay cuts and unfair working conditions went on strike in the summer of 1877. Weeks of violence and chaos between protesters and police wreaked havoc in the North, causing looting and fires, and hundreds of people lost their lives. Eventually, the protests were struck down by the National Guard, and though not much came from the event, it was the first of many flashpoints involving labor rights.

[Pictured: The first meat train to leave the Chicago stockyards during the great railway stikes is escorted by the United States Cavalry.]

Chicago History Museum // Getty Images

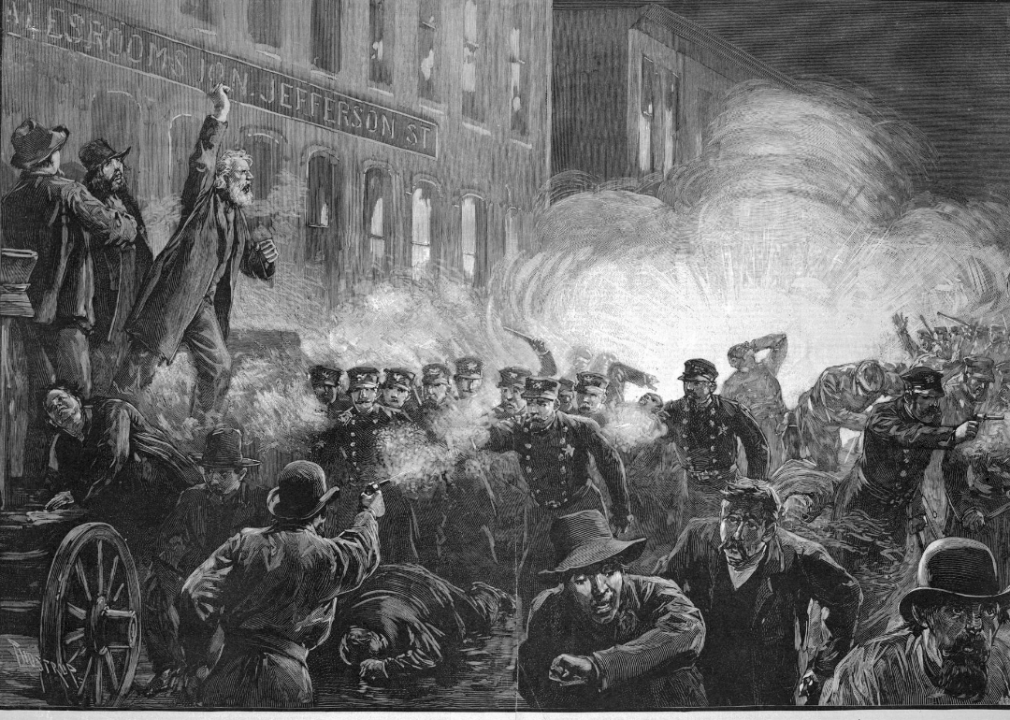

May 4, 1886: Labor leaders, strikers protest police brutality in the Haymarket riots

What began as a peaceful rally in Chicago over the right to eight-hour work days turned into a violent clash between police and protesters. After a display of callousness towards workers’ rights from police officers, protesters shifted their attention toward police brutality. A bomb was thrown to dismantle the protests, and officers fired into the crowd, killing eight people and leaving even more wounded.

[Pictured: The events at Haymarket Square, published in Harper’s Weekly, Chicago, May 15, 1886.]

Unknown // Wikimedia Commons

Sept. 10, 1897: Immigrant miners are attacked in the Lattimer massacre

The Lattimer massacre was one of the bloodiest clashes in American labor history. Unarmed strikers were peacefully protesting labor conditions in the mining industry when police officers opened fire on the line of strikers, killing 19 miners. The massacre quickly caught media attention, and as people learned of this latest instance of police brutality, a new sense of unity toward immigrant miners was born.

[Pictured: The Lattimer massacre.]

Mississippi Department of Archives and History // Wikimedia Commons

1904: Parchman Farm in Mississippi shifts from plantation to prison

Parchman Farm is a former plantation turned prison by the state of Mississippi. After the 13th Amendment abolished slavery, “except as a punishment for crime,” government officials established Black codes in an effort to exploit the continuum of Black suffering. Black people were often harshly punished and incarcerated for breaking fragile rules white people did not have to follow, causing mass incarceration in disproportionate numbers. Prisoners sent to the Parchman Farm experienced harsh labor described as “the closest thing to slavery that survived the Civil War,” having to work sun-up to sundown performing slave duties under the control of armed guards.

[Pictured: Male prisoners on the porch at Parchman Penitentiary.]

Chicago History Museum // Getty Images

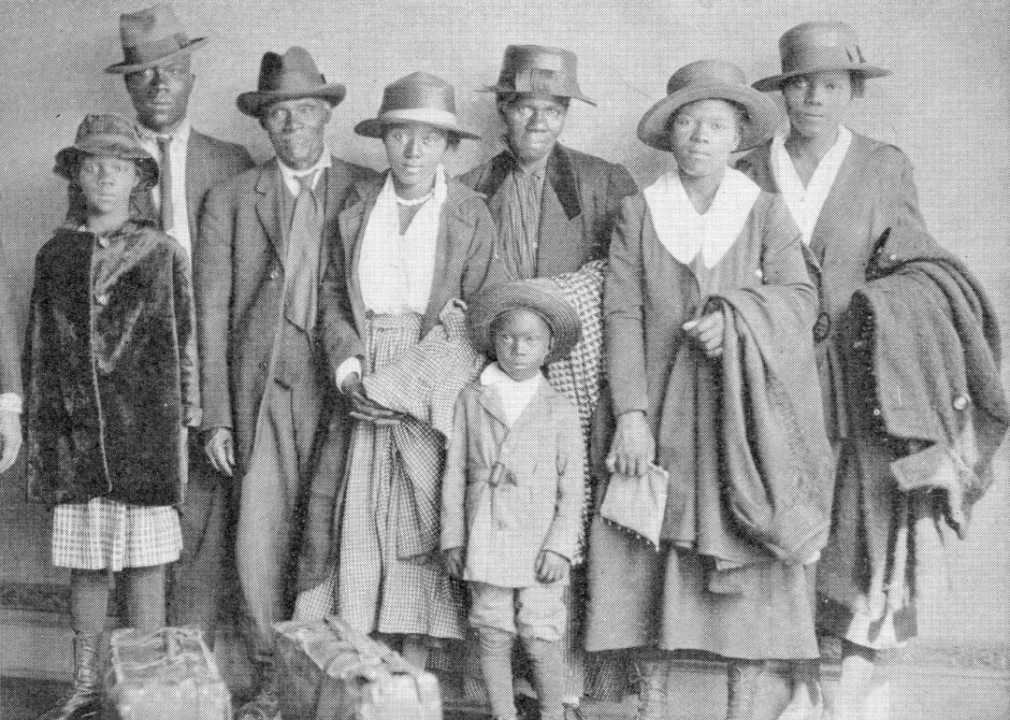

1916: Start of Great Migration causes racial tensions

Millions of African Americans found new life in the North in an effort to escape harsh Jim Crow laws and extreme racial violence, as well as take advantage of job opportunities in what is now known at the Great Migration. This was new to white communities and police departments who were not accustomed to the presence of Black people. They reacted to the staggering increase in numbers with fear and hostility, attitudes that were exacerbated by racist stereotypes.

[Pictured: African American men, women, and children who participated in the Great Migration to the north in Chicago, 1918.]

Tthrail // Wikimedia Commons

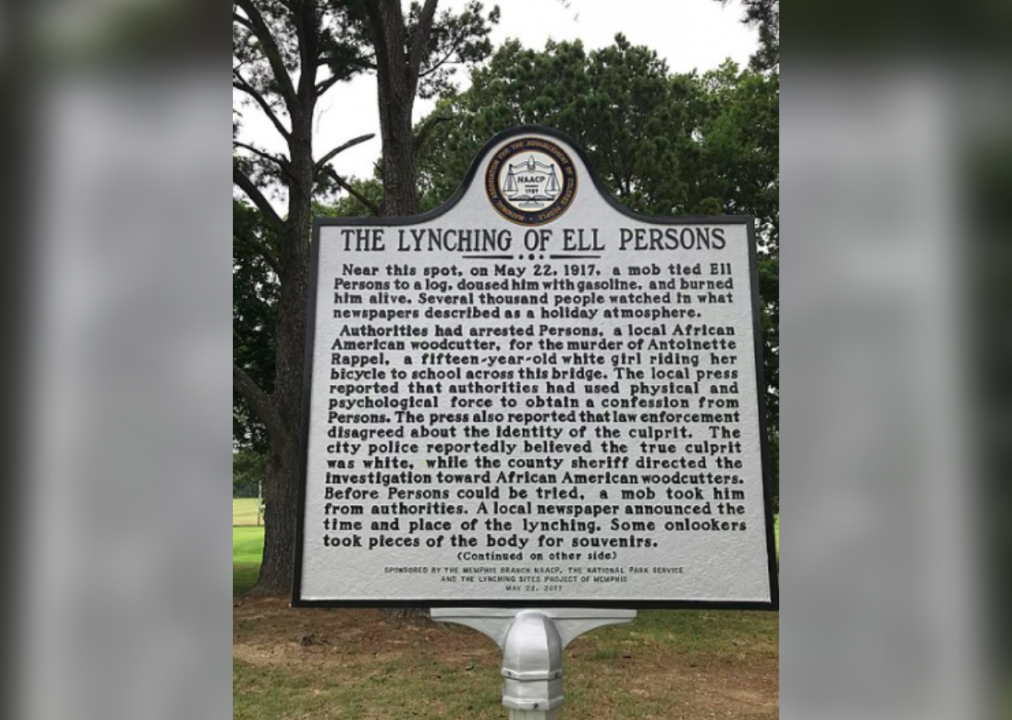

May 22, 1917: Ell Persons lynching

Ell Persons, a Black man in his 50s, was lynched in 1917 after being accused of raping a white teenage girl. After being beaten into a confession, he was doused with gasoline, burned alive, and dismembered in front of thousands of spectators. As it was normal for lynchings to be displayed in front of the white public, sandwiches and snacks were sold at the lynching.

[Pictured: The Ell Persons historical marker in Memphis, Tennessee.]

The West Virginian // Wikimedia Commons

1919: The ‘Red Summer’ of 1919

A Black teenager drowned in Lake Michigan in Chicago after being stoned by a group of young white people for crossing a segregated barrier of the lake. After law officials refused to arrest the white man who eyewitnesses said caused the murder, a riot broke out and lasted for weeks on Chicago’s South Side. Many died, and Black homes were destroyed.

[Pictured: A victim is stoned and bludgeoned under a corner of a house during the 1919 race riots in Chicago.]

Harris & Ewing // Wikimedia Commons

1929: President Herbert Hoover establishes the National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement

The NCLOE or “Wickersham Commission” was designed to investigate crime related to prohibition, in addition to policing tactics. Between 1931 and 1932, the commission published the findings of its investigation in 14 volumes, one of which was titled “Report on Lawlessness in Law Enforcement” and said that police frequently used torture methods to enforce the law. Instead of reform, officials declared a “war on crime” and aimed to militarize the police.

[Pictured: President Hoover meets with his newly created enforcement commission.]

NARA // Wikimedia Commons

May 30, 1937: Chicago police shoot 10 protesters at Republic Steel Plant protests

Laborers continued to fight for their rights well into the early 20th century, and when the Republic Steel Plant’s leaders refused to sign a labor contract for their workers, protests ensued. The Chicago Police Department demanded protesters to disperse, and when they didn’t, the department used tear gas on demonstrators and shot and killed 10 people.

[Pictured: Photograph titled “The Chicago Memorial Day Incident.”]

Anthony Potter Collection // Getty Images

1943: LAPD officers complicit in attacks against Mexican Americans during Zoot Suit Riots

A clash between Mexican Americans and white servicemen broke out, resulting in the death of a U.S sailor. In response, mobs of U.S servicemen carrying weapons brutally attacked anyone wearing a zoot suit, an outfit popular among some Mexican Americans that became a racist stereotype. The attackers went into Latino communities in Los Angeles, stripped people of their clothes and beat them as LAPD often looked on from the sidelines, arresting the victims after the fact.

[Pictured: Gangs of American sailors and marines armed with sticks during the Zoot Suit Riots, Los Angeles, June 1943.]

Bettmann // Getty Images

1882–1968: Lack of law enforcement and government intervention during lynchings and murders

There were 5,000 documented accounts of Black people being lynched across the U.S. South during the Jim Crow era, and it’s been more than 100 years since the first anti-lynching bill was proposed and continues to be debated today. While many Black advocates brought gruesome evidence of the lynchings to the attention of government officials, nothing was done to designate the brutality as a hate crime. And while lynching by definition decreased in numbers in the ’60s, modern-day lynching continues.

[Pictured: Protesters marched on the streets of Washington carrying signs urging control and halting of the lynching of blacks in Washington, 1922.]

Bettmann // Getty Images

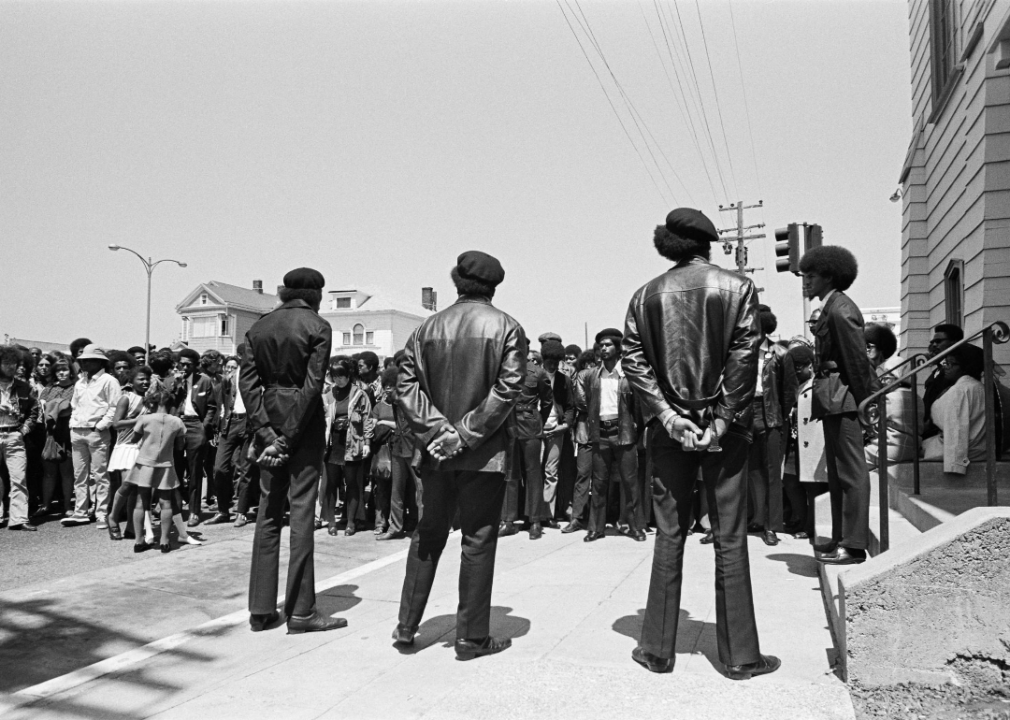

1956: COINTELPRO is founded to monitor radicals and activists

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover encouraged COINTELPRO, a group founded to discredit organizations disruptive to U.S politics, to focus on tools that taught about Black power and warned of a “Black messiah,” or leader of Black nationalism. As a result, the FBI infiltrated Black organizations like the Black Panther Party. Hoover even targeted Black-owned bookstores and their products, as the movement was seen as a threat. An infamous instance of the state suppressing Black power was turned into the movie “Judas and the Black Messiah,” chronicling activist and organizer Fred Hampton’s work toward Black empowerment and forming of the Rainbow Coalition as well as police and FBI targeting, including a police raid in which police shot and killed Hampton.

[Pictrued: John Edgar Hoover, FBI director.]

Hulton Archive // Getty Images

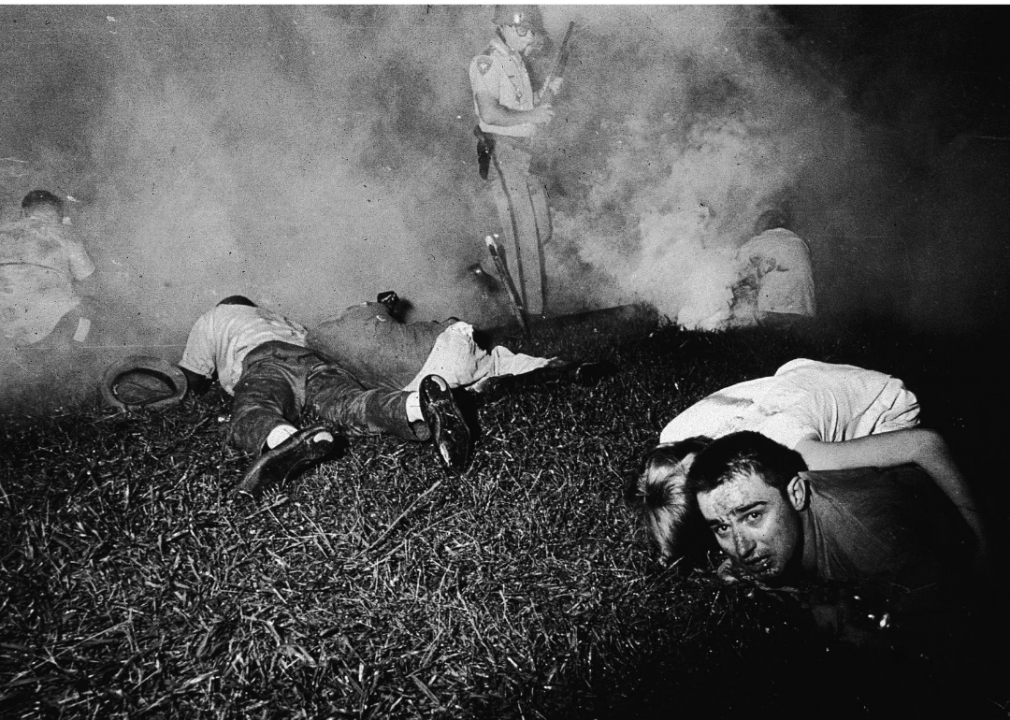

1960s: Rising militarization of police forces around the US

In the civil rights era, police departments around the country started to become more and more militarized. The first SWAT team emerged in Los Angeles during this time after a series of high-profile raids against groups like the Black Panther Party. Soon, SWAT teams spread across the country, and the federal government began to blur the lines between soldiers and policemen.

[Pictured: Civil rights marchers stay close to the ground as Mississippi Highway Patrolmen use tear gas on the protestors, Canton, Mississippi, 1960s.]

PhotoQuest // Getty Images

1963: Over 250,000 attend March on Washington

One of the most well-known moments in civil rights history, the March on Washington was a nationwide outcry from Black Americans who marched to stop racial discrimination and police brutality and gain job equality. The emotional event is where Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

[Pictured: Martin Luther King Jr. addresses the crowd on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial during the historic March on Washington.]

Hulton Archive // Getty Images

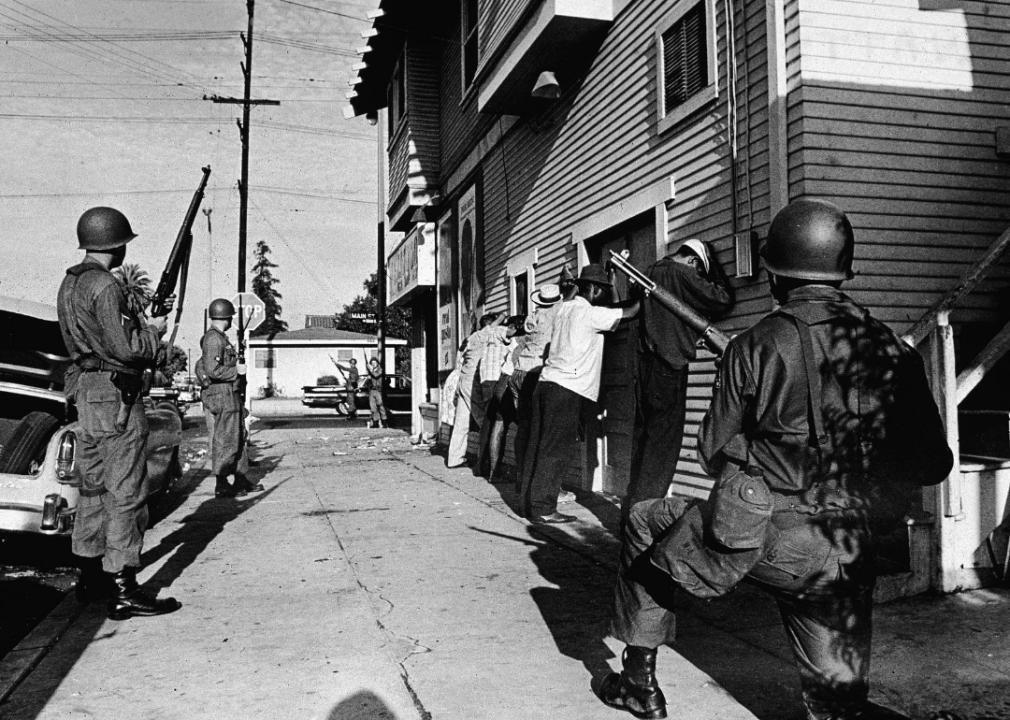

1965: Watts Riots highlight tensions between police and Black Americans

A young Black motorist named Marquette Frye was pulled over by police for suspicion of being intoxicated. Onlookers gathered as racial tensions between the Black community and law enforcement ran high. As things grew more contentious between the two groups, more police officers rushed to the scene, and violence ensued, leading to a six-day riot.

[Pictured: Armed National Guardsmen force a line of Black men to stand against the wall of a building during the Watts race riots, Los Angeles, August 1965.]

Harry Benson // Getty Images

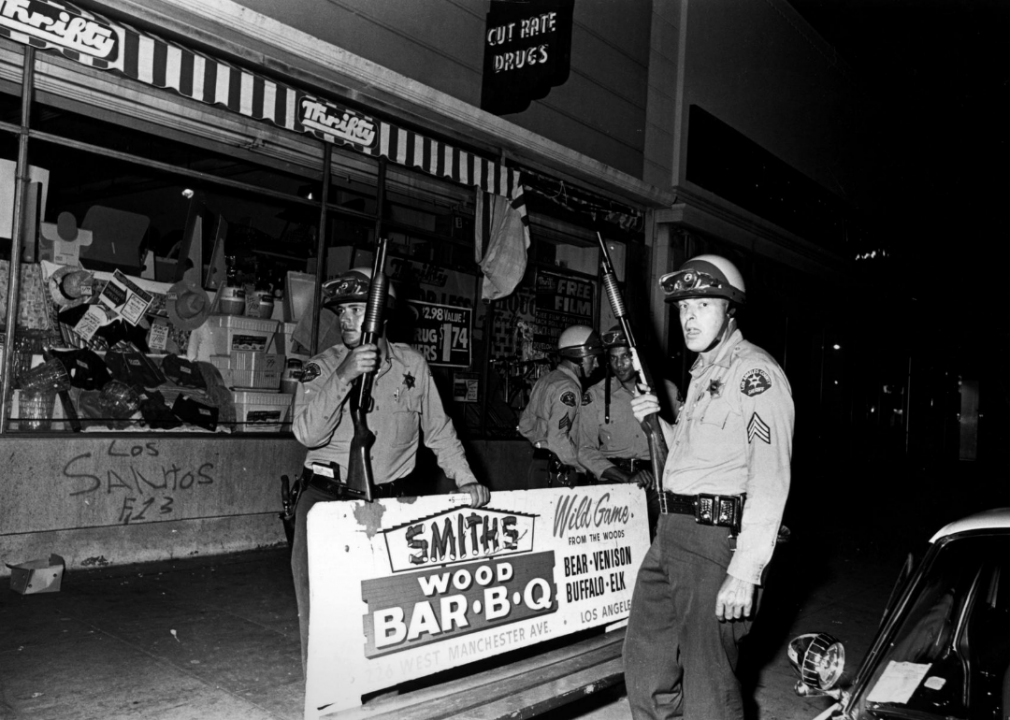

1965: Special Weapons and SWAT team established in LA

LAPD established the “Special Weapons and Tactics,” or SWAT teams, in response to the Watts uprisings that year, militarizing police tactics. The program expanded across the country and was used heavily to quash riots and enforce military order over any uprisings.

[Pictured: Armed police patrolling the streets of Los Angeles during the Watts race riots.]

New York Times Co. // Getty Images

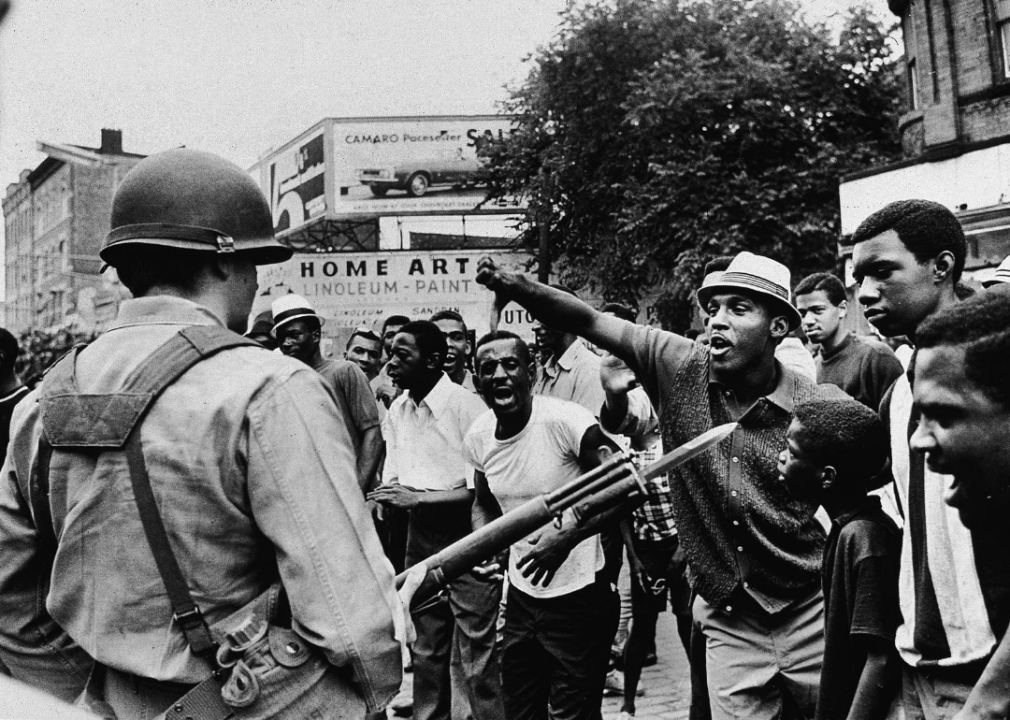

1967: Newark race riot begins due to injuries inflicted by police on John Smith

The Newark race riot began when white police officers severely beat a Black cab driver named John Smith during a traffic stop. The protest against the police brutality turned violent, and 26 people died, with many others injured during the four-day clash.

[Pictured: A man gestures with his thumb down to an armed National Guardman, during a protest in the Newark race riots, Newark, New Jersey, July 14, 1967.]

AFP // Getty Images

1967: Racial profiling and police brutality culminate in Detroit riots

The Detroit Riots are considered among the most destructive in American history. After incidents of “white flight,” where white people fled to suburban areas after Black people integrated Detroit’s urban areas, the area was densely populated with African Americans and heavily policed. Police conducted a bar raid, and while they were making arrests, a riot broke out that lasted for days.

[Pictured: A federal soldier stands guard in a Detroit street on July 25, 1967, as buildings are burning.]

Underwood Archives // Getty Images

1967: Federal Kerner Commission admits that ‘police action’ is the cause of urban rebellions of 1960s

In 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson organized the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (also called the Kerner Commission) to investigate the causes of recent major riots. The commission found common denominators at the heart of many protests/rebellions of the ’60s: white racism and police brutality. However, conservative Americans and Johnson did not eagerly accept these findings.

[Pictured: The Kerner Commission in session, Washington D.C., 1967.]

Unknown // Wikimedia Commons

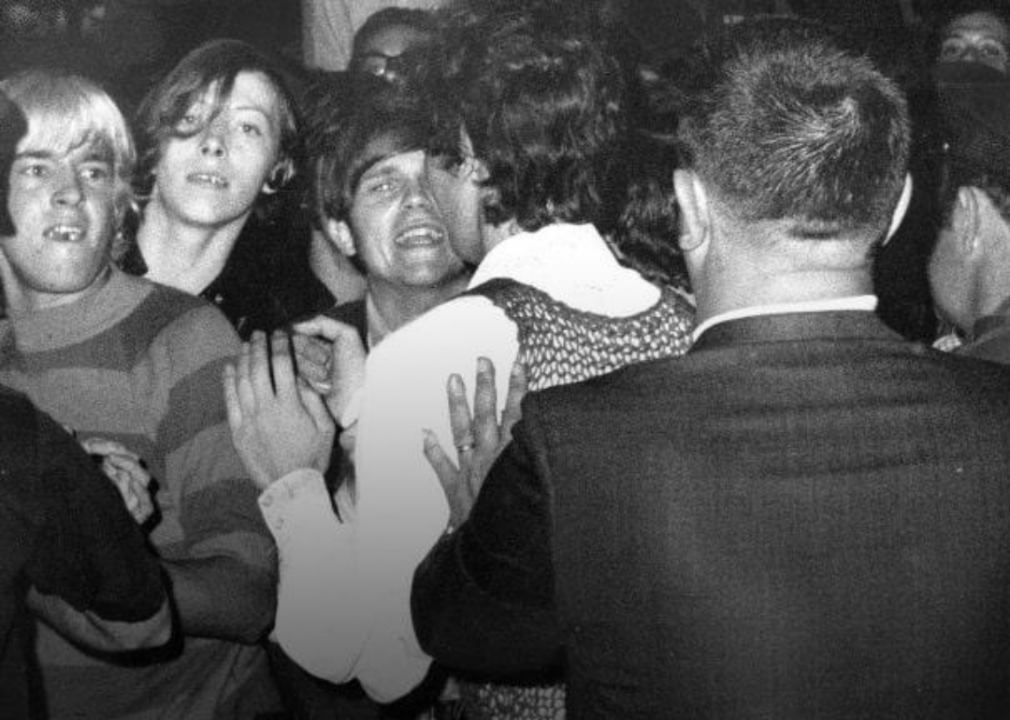

1969: New York City riots after a police raid on Stonewall Inn

On the night of June 27, 1969, members of the LGBTQ+ community were visiting the Stonewall Inn, one of the few openly LGBTQ-friendly bars in New York City, when the police raided it. Fed up with being marginalized, members and allies of the community gathered by the hundreds to riot in protest of police harassment, galvanizing the gay rights movement.

[Pictured: Police force people back outside the Stonewall Inn as tensions escalate the morning of June 28, 1969.]

Harold Adler/Underwood Archives // Getty Images

1971: Death of George Jackson in prison sparks controversy

George Jackson was a Black activist and author who was imprisoned in 1959 for stealing $70 from a gas station and killed in an alleged escape attempt. He organized sit-ins against the segregated cafeterias and taught martial arts to fight back against abusive prison guards. A member and leader of the Black Panther Party, Jackson had achieved worldwide fame for writing “Soledad Brother” while in prison.

[Pictured: The funeral of Black Panther George Jackson at St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church, Oakland, California, 1971.]

Bill Wunsch // Getty Images

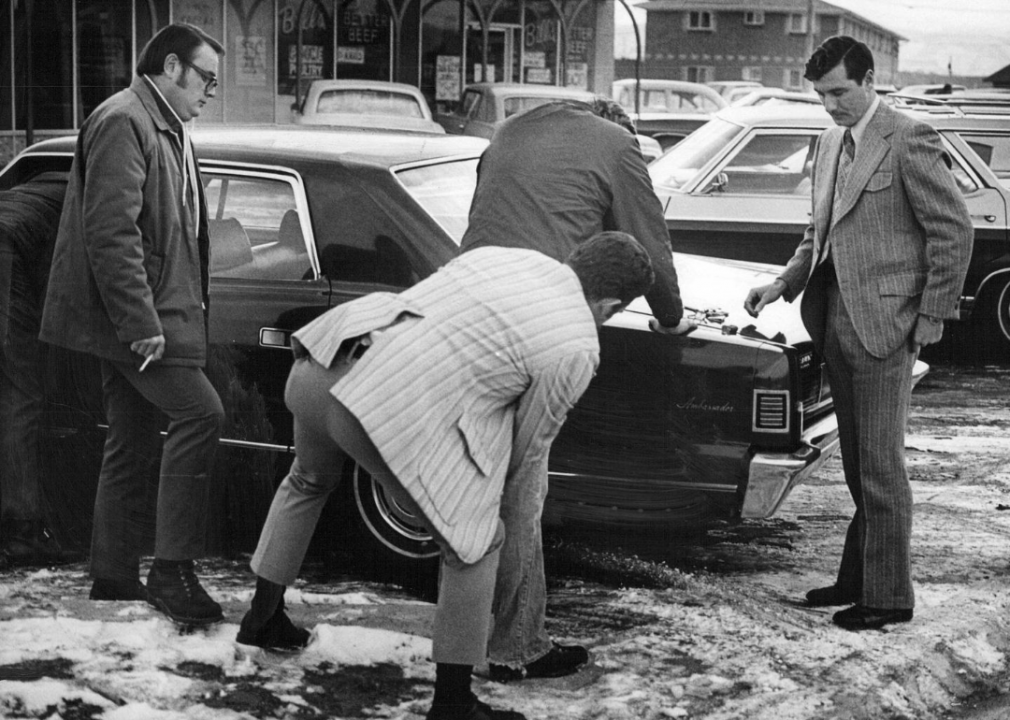

June 18, 1971: War on drugs campaign kicks off

The war on drugs was used as a justification for increased policing and arrests and harsher prison sentences, largely targeting Black communities. Former Nixon-era domestic policy chief John Ehrlichman later confirmed that the effort was designed to hurt Black families.

[Pictured: Suspect frisked after arrest in drug raid in Colorado in 1971.]

Bettmann // Getty Images

1970s–1980s: Spike in urban crime perpetuates stereotypes and creates ‘broken windows’ policies

With institutionalized racism in place, incarceration numbers and urban crime rates began to rise in the 1970s and ’80s, further perpetuating stereotypes. The “broken windows” theory was introduced during this time, which stated that small crimes would lead to bigger crimes if not punished. Police took license to enforce punishments on small “offenses” like jaywalking or unauthorized barbecues.

[Pictured: Police officer holds a “suspect” on a car in New York City, 1980.]

ATOMIC Hot Links // Flickr

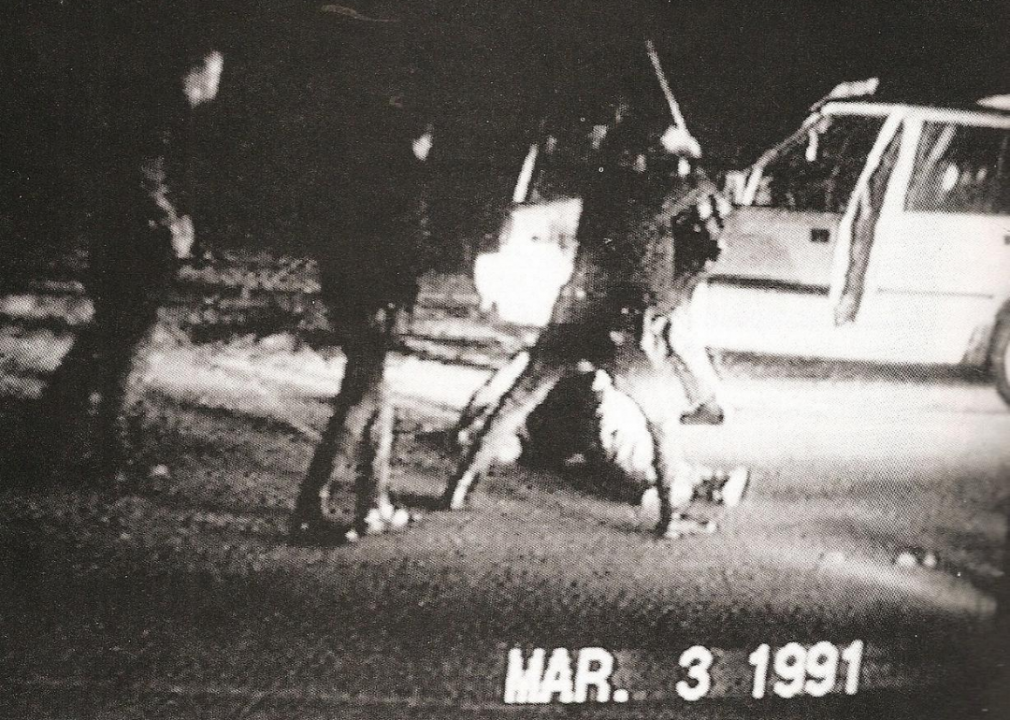

1991: Video of police officers beating Rodney King sparks outrage

Video evidence of three policemen brutally beating 25-year-old Rodney King made its way around the country. The acquittal of all four officers involved (three of them white) sparked riots and protests across Los Angeles due to widespread anger and frustration with LAPD violence toward the city’s Black community.

[Pictured: Nationally televised footage of the Rodney King beating.]

Donaldson Collection // Getty Images

1992: Riots begin in Los Angeles due to Rodney King beating and Latasha Harlins killing

Along with the acquittal of the officers in the Rodney King case, another incident is thought to have helped fuel the L.A. Riots. In March 1991, 15-year-old Latasha Harlins was fatally shot in the back of the head by a Korean store owner after she was accused of stealing juice. Harlins had money in her hand at the time of the shooting. The store owner received probation and a $500 fine.

[Pictured: LAPD officers arrest rioters on April 29, 1992.]

Richard Baker // Getty Images Images

1994: Congress passes the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994

This crime bill called for the Department of Justice “to review the practices of law enforcement agencies that may be violating people’s federal rights.” While the bill was intended to signal an effort to reform police departments, it ultimately caused more harm than good for low-income Black families by enforcing “tough on crime” provisions.

[Pictured: A 1990s Atlanta police officer shines his flashlight into the face of a man lying on the ground.]

Andrew Lichtenstein // Getty Images

1994: Violent Crime bill’s “three strikes” provisions pave way for mass incarceration

The Clinton administration’s 1994 crime bill encouraged strict law enforcement and caused the system to target more Black and Latinx Americans who would ultimately fall victim to mass incarceration. An entire portion of the bill highlighted “tough punishment” like the bill’s “three strike” rule, which implemented life sentences for people who already had two other offenses under their belt.

[Pictured: People under arrest by narcotics police in Bridgeport, Connecticut, in 1994.]

Spencer Platt // Getty Images

1997: 1033 program helping to militarize police is created

The 1033 program was a military equipment loan program that incorporated military weapons like grenade launchers in police departments in almost every state in America. This further heightened the use of military assault rifles during public calls to action such as protests or riots.

[Pictured: An armed NYPD officer guards the New York Stock Exchange, Aug. 2, 2004.]

Jonathan Elderfield // Getty Images

Feb. 4, 1999: Police shooting of Amadou Diallo

Amadou Diallo was a 23-year-old Black man who was shot and killed by policemen. Police shot at Diallo 41 times and hit him with 19, claiming to have seen a gun—which turned out to be his wallet. All policemen involved were acquitted, after which thousands of protestors participated in a mostly peaceful march.

[Pictured: Protestors hold up signs in front of a New York City judicial building, Feb. 9, 1999.]

sakhorn // Shutterstock

2000: Prison population almost doubles in a single decade

DOJ statistics show that about 1.39 million people were incarcerated in the year 2000, as opposed to about 774,000 in 1990. By 2018, Black men were over fives times more likely to be imprisoned than white men, and Black women were imprisoned 1.8 more times than white women.

Benedek Alpar // Shutterstock

2000s: School-to-prison pipeline emerges with increased police presence and zero-tolerance policies in schools

Racial punishment merged with public education with the “School to Prison Pipeline” system, in which students are pushed out of schools and into the hands of law enforcement. The increased use of juvenile detentions came as a result of the new disciplinary reaction to students, predominantly of color, and often used harsh punishment tactics.

Mike Simons // Getty Images

April 7, 2001: Cincinnati police officer shoots Timothy Thomas

White police officer Stephen Roach shot and killed 19-year-old Timothy Thomas, who was unarmed, in a dark alley. He was acquitted after the judge ruled that Roach’s response was “reasonable.” Protesters took to the streets in response to the killing, and demonstrators warned, “No justice, no peace.” It was one of the greatest fights against racial discrimination and police brutality since the civil rights movement.

[Pictured: A protester holds up a sign May 7, 2001, in Cincinnati, Ohio.]

Allison Joyce // Getty Images

2001–2013: NYC police target people of color due to 9/11 and expansion of ‘stop and frisk’

Shortly after 9/11, New York City began implementing a new program called “stop and frisk.” The policy allowed officers to stop and question people they felt were suspicious of criminal activity, resulting in racial profiling and police violence. Michael Bloomberg, the mayor of NYC at the time, apologized for promoting the policy during his 2020 presidential bid.

[Pictured: New York City Police officers watch over a demonstration against the city’s “stop and frisk” searches in 2013.]

Allan Tannenbaum // Getty Images

2002: NYPD’s Street Crimes Unit disbanded

Largely due to the shooting of Amadou Diallo, the NYPD’s Street Crimes Unit had been criticized for singling out Blacks and Hispanics—all four of the police involved in the Diallo shooting were on the Street Crimes Unit. The police commissioner at the time, Raymond W. Kelly, claimed that the unit’s closing had little to do with changes in policy and more with a general restructuring of the force.

[Pictured: Shrine at the home of Amadou Diallo, Feb. 25, 2000.]

Spencer Platt // Getty Images

2006: Police shootings of Sean Bell and Kathryn Harris Johnston further escalate tensions

92-year-old Kathryn Johnston stood in her doorway with a revolver after police forced their way into her home with a “no-knock” warrant aiming to carry out a drug bust. Johnston shot three of the officers and was shot and killed. The neighborhood went into an uproar, as neighbors believed Johnston to be using self defense. In another incident, Sean Bell was shot at 50 times in Queens when he was killed; none of the officers were charged with the killing.

[Pictured: Police keep watch over demonstrators in the street after the verdict was announced in the Bell shooting trial April 25, 2008, in New York City.]

Michael Nagle // Getty Images

2007: Under pressure, NYPD releases data showing racial disparities in its policing

After being pushed to do so by advocates and officials, the NYPD released records that showed disparities in police shootings over the years. Records showed that more than half the people stopped by police were Black, and many believed it to be a result of the “stop and frisk” policy implemented in the years prior. The statistics showed that Black people were 23% more likely to be stopped by police than white people were, and for the Latinx community, it was even higher at 39%.

[Pictured: NYPD officers in the area around Times Square on June 29, 2007, in New York City.]

NurPhoto // Getty Images

Dec. 20, 2011: Police shooting of Anthony Lamar Smith

24-year-old Anthony Lamar Smith was shot and killed by a white police officer, Jason Stockley, after a car chase, an incident that sparked protest in 2017 when the officer was acquitted. In the police footage of the chase, Stockley is heard saying, “We’re killing this motherf–ker, don’t you know.” The St. Louis police settled a wrongful death lawsuit in 2013 with Smith’s family for $900,000, a sum later increased to $1.4 million.

[Pictured: Protests following the not guilty verdict in Jason Stockley’s trial.]

Ted Eytan // Flickr

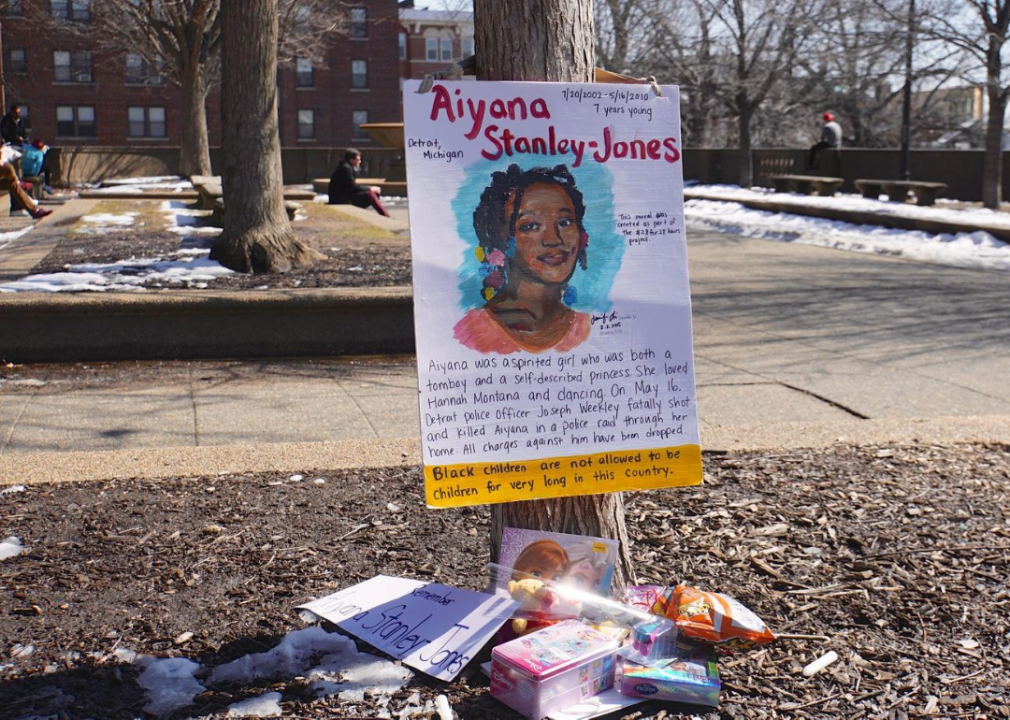

May 16, 2010: SWAT shooting of 7-year-old Aiyana Jones

Aiyana Stanley-Jones was a 7-year-old Black girl who was shot in the head during a SWAT operation in the middle of the night. This incident sparked outrage over growing militarization of police forces in the country, as well as the racial disparities between the police and Black communities. Charges against the officer who shot her were dropped in 2015.

[Pictured: Memorial to Aiyana Jones.]

Michael B. Thomas // Getty Images

2014: Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, and Michael Brown all die at the hands of police

After the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, the Black Lives Matter movement drew national attention and highlighted the racial disctimination and police brutality that occurs often in Black communities. Furthermore, social media brought to light video evidence of multiple killings that summer, including Eric Garner in New York, who was killed by a chokehold, and 12-year-old Tamir Rice, who was shot by police while playing with a toy gun. Protests erupted across the country amid calls for police reform.

[Pictured: Protest of the shooting death of Michael Brown outside Ferguson Police Department Headquarters, Aug. 11, 2014, in Ferguson, Missouri.]

Anadolu Agency // Getty Images

Nov. 28, 2014: UN Committee against Torture condemns police brutality and excessive use of force by law enforcement in the US

The UN Committee Against Torture called for action against police brutality in Black communities in an effort to decrease the killing of unarmed Black people and stop the use of military weapons during protest. The committee claimed to have “numerous reports” on the use of excessive police brutality, specifically in minority groups, and encouraged investigations to be launched.

[Pictured: Teenagers protest during the United Nations Committee Against Torture in Geneva, Switzerland, on Nov. 13, 2014.]

Andrew Burton // Getty Images

2015: Deaths of Freddie Gray and shooting of Keith Childress Jr. raise questions

By this time, some members of the Black community were exhausted from being traumatized by filmed evidence of police violence. In the midst of this, Freddie Gray, a Black man who was being held in the back of a police van for possession of a knife, died from injuries to his spinal cord. Keith Childress Jr. was shot and killed after his cellphone was allegedly mistaken for a gun by police officers.

[Pictured: Riot police stand guard after the funeral of Freddie Gray, on April 28, 2015, in Baltimore, Maryland.]

KENA BETANCUR // Getty Images

July 13, 2015: Sandra Bland is found dead after being arrested during a traffic stop

Sandra Bland was a 28-year-old Black woman who was taken into custody after being pulled over for a traffic stop in 2015. The stop turned confrontational, and Bland was tackled to the ground and put in cuffs, all of which was captured on police cameras and by Bland herself on her phone. She was found dead soon after the incident in her cell, and her death was deemed a suicide. The Black Lives Matter movement was becoming widespread and pushing stories like Bland’s into greater media attention as outrage intensified over unfair treatment, racial biases, and disregard for safety during arrests by law enforcement.

[Pictured: A woman holds a poster of Sandra Bland during a Michael Brown memorial rally on Union Square, Aug. 9, 2015, in New York.]

Stephen Maturen // Getty Images

July 2016: Police shootings of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling happen just a day apart

In 2016, Castile and Sterling were two of 233 African Americans shot and killed by police. These numbers startled many, considering African Americans make up 13% of the U.S. population but account for 24% of people fatally shot by police that year. Just days apart from each other, two Black men, Philando Castile and Alton Sterling, were shot under police custody.

[Pictured: Demonstrators march in honor of Philando Castile on July 6, 2020, in St. Anthony, Minnesota.]

BENOIT DOPPAGNE // Getty Images

September 2016: UN’s Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent issues scathing report on police killings

After seeing multiple recordings of Black lives taken away by the hands of law enforcement, activists and officials began to demand acknowledgement, reparations, and consequences for past and present acts of “enslavement, racial subordination and segregation, racial terrorism and racial inequality.” In a statement, the UN group compared the trauma of police killings to the horror of lynchings in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

[Pictured: Press conference, in Brussels on Feb. 11, 2019, on the preliminary findings of the United Nations Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent’s delegation.]

BING GUAN // Getty Images

2017–2020: Trump administration peels back Justice Department programs that investigate local police departments for racism and excessive force

During the Obama administration, police reform programs were underway to find solutions to the racial tension involving law enforcement. The Department of Justice essentially limited their efforts on behalf of this reform model when the Trump administration took over. Due to this, many people criticized the new administration for abandoning the reform efforts, accusing them of taking police brutality lightly.

[Pictured: Officers separate right-wing counter-protestors from Black Lives Matter demonstrators in La Mesa, California, on Aug. 1, 2020.]

Ira L. Black/Corbis // Getty Images

May 2020: Deaths of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd reignite worldwide protests against police brutality and racism

The killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and more Black people at the hands of police brought worldwide protests and calls for change. Simply put, Black people were tired and outraged by the lack of care for Black lives and the continued display of racial violence by police, with little to no reform or consequences. In the midst of a global pandemic, protests continued to take place, along with calls to defund the police by reallocating funds for things like social services, crisis mediation, and other means of community assistance.

[Pictured: Crowds pass the New York Police Department office in Times Square in New York City on July 26, 2020.]

You may also like: How America has changed since the first Census in 1790